'We all suffer from PTSD': 10 years after the Costa Concordia cruise disaster, memories remain

GIGLIO, Italy — Ten years have passed since the Costa Concordia cruise ship slammed into a reef and capsized off the Tuscan island of Giglio. But for the passengers on board and the residents who welcomed them ashore, the memories of that harrowing, freezing night remain vividly etched into their minds.

The dinner plates that flew off the tables when the rocks first gashed the hull. The blackout after the ship's engine room flooded and its generators failed. The final mad scramble to evacuate the listing liner and then the extraordinary generosity of Giglio islanders who offered shoes, sweatshirts and shelter until the sun rose and passengers were ferried to the mainland.

Italy on Thursday is marking the 10th anniversary of the Concordia disaster with a daylong commemoration that will end with a candlelit vigil near the moment the ship hit the reef: 9:45 p.m. on Jan. 13, 2012. The events will honor the 32 people who died that night, the 4,200 survivors, but also the residents of Giglio, who took in passengers and crew and then lived with the Concordia's wrecked carcass off their shore for another two years until it was righted and hauled away for scrap.

► CDC travel guidance: CDC warns 'avoid cruise travel' after more than 5,000 COVID cases in two weeks amid omicron

“For us islanders, when we remember some event, we always refer to whether it was before or after the Concordia,” said Matteo Coppa, who was 23 and fishing on the jetty when the darkened Concordia listed toward shore and then collapsed onto its side in the water.

“I imagine it like a nail stuck to the wall that marks that date, as a before and after,” he said, recounting how he joined the rescue effort that night, helping pull ashore the dazed, injured and freezing passengers from lifeboats.

The sad anniversary comes as the cruise industry, shut down in much of the world for months because of the coronavirus pandemic, is once again in the spotlight because of COVID-19 outbreaks that threaten passenger safety. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control last month warned people across-the-board not to go on cruises, regardless of their vaccination status, because of the risks of infection.

► 'We found out while we were flying': Last-minute cruise cancellations leave travelers scrambling

► 'The Disney magic is gone' ... or is it?: Longtime fans weigh in on changes at Disney World

'We all suffer from PTSD'

For Concordia survivor Georgia Ananias, the COVID-19 infections are just the latest evidence that passenger safety still isn’t a top priority for the cruise ship industry. Passengers aboard the Concordia were largely left on their own to find life jackets and a functioning lifeboat after the captain steered the ship close too shore in a stunt. He then delayed an evacuation order until it was too late, with lifeboats unable to lower because the ship was listing too heavily.

“I always said this will not define me, but you have no choice," Ananias said in an interview from her home in Los Angeles, Calif. “We all suffer from PTSD. We had a lot of guilt that we survived and 32 other people died.”

Prosecutors blamed the delayed evacuation order and conflicting instructions given by crew for the chaos that ensued as passengers scrambled to get off the ship. The captain, Francesco Schettino, is serving a 16-year prison sentence for manslaughter, causing a shipwreck and abandoning a ship before all the passengers and crew had evacuated.

Ananias and her family declined Costa’s initial $14,500 compensation offered to each passenger and sued Costa, a unit of U.S.-based Carnival Corp., to try to cover the cost of their medical bills and therapy for the post-traumatic stress they have suffered. But after eight years in the U.S. and then Italian court system, they lost their case.

“I think people need to be aware that when you go on a cruise, that if there is a problem, you will not have the justice that you may be used to in the country in which you are living,” said Ananias, who went onto become a top official in the International Cruise Victims association, an advocacy group that lobbies to improve safety aboard ships and increase transparency and accountability in the industry.

Costa didn’t respond to emails seeking comment on the anniversary.

► Royal Caribbean cancels sailings: Pushes back restart on several ships over COVID

'We did something incredible'

Cruise Lines International Association, the world’s largest cruise industry trade association, stressed in a statement to The Associated Press that passenger and crew safety was the industry's top priority, and that cruising remains one of the safest vacation experiences available.

“Our thoughts continue to be with the victims of the Concordia tragedy and their families on this sad anniversary," CLIA said. It said it has worked over the past 10 years with the International Maritime Organization and the maritime industry to “drive a safety culture that is based on continuous improvement."

For Giglio Mayor Sergio Ortelli, the memories of that night run the gamut: the horror of seeing the capsized ship, the scramble to coordinate rescue services on shore, the recovery of the first bodies and then the pride that islanders rose to the occasion to tend to the survivors.

► Cruising during COVID-19: Cancellation, refund policies vary by cruise line

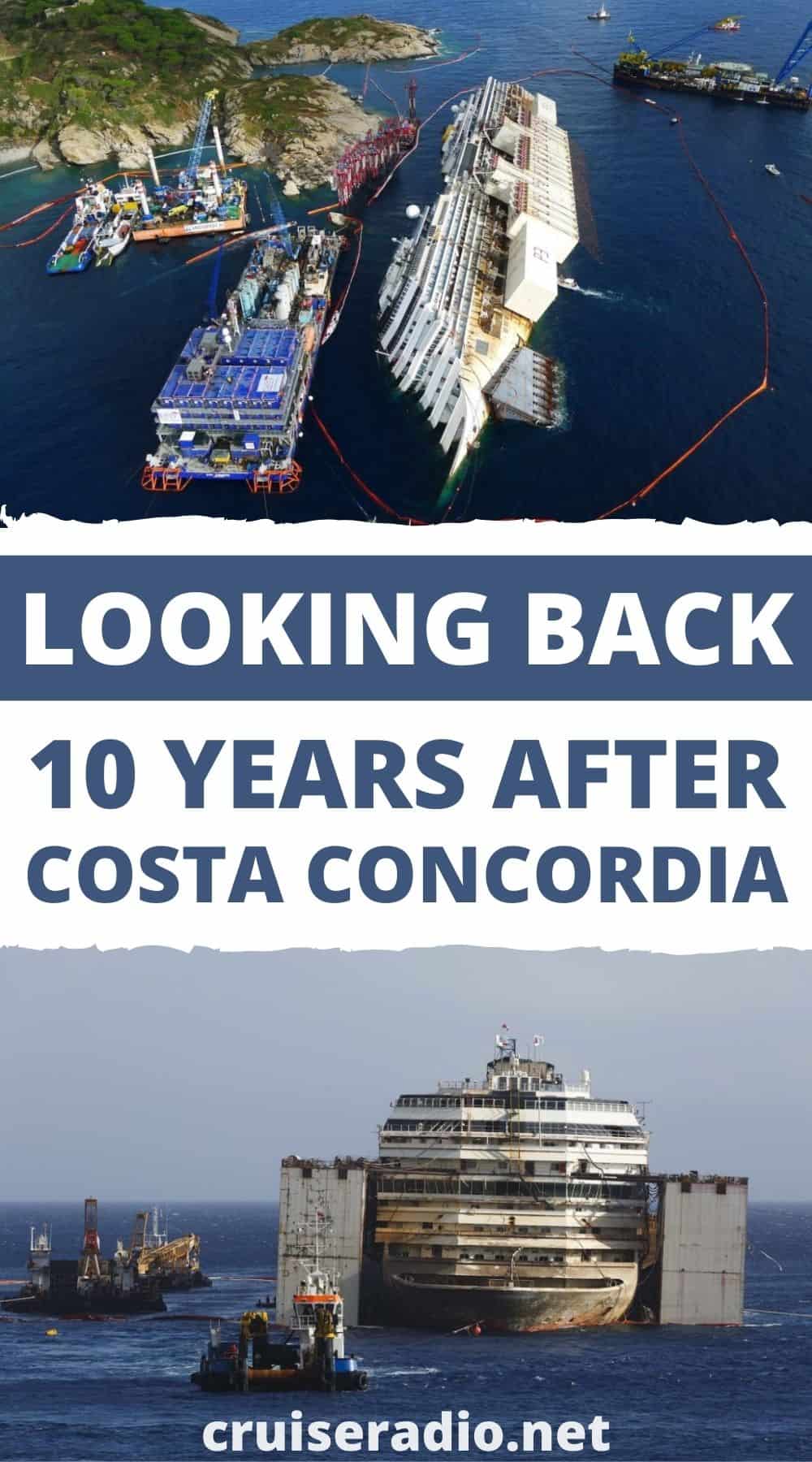

Ortelli was later on hand when, in September 2013, the 115,000-ton, 1,000-foot long cruise ship was righted vertical off its seabed graveyard in an extraordinary feat of engineering. But the night of the disaster, a Friday the 13th, remains seared in his memory.

“It was a night that, in addition to being a tragedy, had a beautiful side because the response of the people was a spontaneous gesture that was appreciated around the world,” Ortelli said.

It seemed the natural thing to do at the time. “But then we realized that on that night, in just a few hours, we did something incredible.”

Oprah Daily's Beauty O'Wards are here! Shop picks for aging well, from $5

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

- TODAY Plaza

10 years later, Costa Concordia survivors share their stories from doomed cruise ship

Ten years after the deadly Costa Concordia cruise line disaster in Italy, survivors still vividly remember scenes of chaos they say were like something straight out of the movie "Titanic."

NBC News correspondent Kelly Cobiella caught up with a group of survivors on TODAY Wednesday, a decade after they escaped a maritime disaster that claimed the lives of 32 people. The Italian cruise ship ran aground off the tiny Italian island of Giglio after striking an underground rock and capsizing.

"I think it’s the panic, the feeling of panic, is what’s carried through over 10 years," Ian Donoff, who was on the cruise with his wife Janice for their honeymoon, told Cobiella. "And it’s just as strong now."

More than 4,000 passengers and crew were on board when the ship crashed into rocks in the dark in the Mediterranean Sea, sending seawater rushing into the vessel as people scrambled for their lives.

The ship's captain, Francesco Schettino, had been performing a sail-past salute of Giglio when he steered the ship too close to the island and hit the jagged reef, opening a 230-foot gash in the side of the cruise liner.

Passengers struggled to escape in the darkness, clambering to get to the life boats. Alaska resident Nate Lukes was with his wife, Cary, and their four daughters aboard the ship and remembers the chaos that ensued as the ship started to sink.

"There was really a melee there is the best way to describe it," he told Cobiella. "It's very similar to the movie 'Titanic.' People were jumping onto the top of the lifeboats and pushing down women and children to try to get to them."

The lifeboats wouldn't drop down because the ship was tilted on its side, leaving hundreds of passengers stranded on the side of the ship for hours in the cold. People were left to clamber down a rope ladder over a distance equivalent to 11 stories.

"Everybody was rushing for the lifeboats," Nate Lukes said. "I felt like (my daughters) were going to get trampled, and putting my arms around them and just holding them together and letting the sea of people go by us."

Schettino was convicted of multiple manslaughter as well as abandoning ship after leaving before all the passengers had reached safety. He is now serving a 16-year prison sentence .

It took nearly two years for the damaged ship to be raised from its side before it was towed away to be scrapped.

The calamity caused changes in the cruise industry like carrying more lifejackets and holding emergency drills before leaving port.

A decade after that harrowing night, the survivors are grateful to have made it out alive. None of the survivors who spoke with Cobiella have been on a cruise since that day.

"I said that if we survive this, then our marriage will have to survive forever," Ian Donoff said.

Scott Stump is a trending reporter and the writer of the daily newsletter This is TODAY (which you should subscribe to here! ) that brings the day's news, health tips, parenting stories, recipes and a daily delight right to your inbox. He has been a regular contributor for TODAY.com since 2011, producing features and news for pop culture, parents, politics, health, style, food and pretty much everything else.

10 years later, Costa Concordia disaster is still vivid for survivors

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Ten years have passed since the Costa Concordia cruise ship slammed into a reef and capsized off the Tuscan island of Giglio . But for the passengers on board and the residents who welcomed them ashore, the memories of that harrowing, freezing night remain vividly etched into their minds.

The dinner plates that flew off the tables when the rocks first gashed the hull. The blackout after the ship’s engine room flooded and its generators failed. The final mad scramble to evacuate the listing liner and then the extraordinary generosity of Giglio islanders who offered shoes, sweatshirts and shelter until the sun rose and passengers were ferried to the mainland.

Italy on Thursday is marking the 10th anniversary of the Concordia disaster with a daylong commemoration that will end with a candlelit vigil near the moment the ship hit the reef: 9:45 p.m. on Jan. 13, 2012. The events will honor the 32 people who died that night, the 4,200 survivors, but also the residents of Giglio, who took in passengers and crew and then lived with the Concordia’s wrecked carcass off their shore for another two years until it was righted and hauled away for scrap.

“For us islanders, when we remember some event, we always refer to whether it was before or after the Concordia,” said Matteo Coppa, who was 23 and fishing on the jetty when the darkened Concordia listed toward shore and then collapsed onto its side in the water.

“I imagine it like a nail stuck to the wall that marks that date, as a before and after,” he said, recounting how he joined the rescue effort that night, helping pull ashore the dazed, injured and freezing passengers from lifeboats.

The sad anniversary comes as the cruise industry, shut down in much of the world for months because of the coronavirus pandemic, is once again in the spotlight because of COVID-19 outbreaks that threaten passenger safety. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control last month warned people across-the-board not to go on cruises , regardless of their vaccination status, because of the risks of infection.

A dozen passengers on cruise ship test positive for coronavirus

The passengers, whose infections were found through random testing, were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms, according to the Port of San Francisco.

Jan. 7, 2022

For Concordia survivor Georgia Ananias, the COVID-19 infections are just the latest evidence that passenger safety still isn’t a top priority for the cruise ship industry. Passengers aboard the Concordia were largely left on their own to find life jackets and a functioning lifeboat after the captain steered the ship close too shore in a stunt. He then delayed an evacuation order until it was too late, with lifeboats unable to lower because the ship was listing too heavily.

“I always said this will not define me, but you have no choice,” Ananias said in an interview from her home in Los Angeles. “We all suffer from PTSD. We had a lot of guilt that we survived and 32 other people died.”

Prosecutors blamed the delayed evacuation order and conflicting instructions given by crew for the chaos that ensued as passengers scrambled to get off the ship. The captain, Francesco Schettino, is serving a 16-year prison sentence for manslaughter, causing a shipwreck and abandoning a ship before all the passengers and crew had evacuated.

Ananias and her family declined Costa’s initial $14,500 compensation offered to each passenger and sued Costa, a unit of U.S.-based Carnival Corp., to try to cover the cost of their medical bills and therapy for the post-traumatic stress they have suffered. But after eight years in the U.S. and then Italian court system, they lost their case.

“I think people need to be aware that when you go on a cruise, that if there is a problem, you will not have the justice that you may be used to in the country in which you are living,” said Ananias, who went onto become a top official in the International Cruise Victims association, an advocacy group that lobbies to improve safety aboard ships and increase transparency and accountability in the industry.

Costa didn’t respond to emails seeking comment on the anniversary.

Cruise Lines International Assn., the world’s largest cruise industry trade association, stressed in a statement to the Associated Press that passenger and crew safety were the industry’s top priority, and that cruising remains one of the safest vacation experiences available.

“Our thoughts continue to be with the victims of the Concordia tragedy and their families on this sad anniversary,” CLIA said. It said it has worked over the past 10 years with the International Maritime Organization and the maritime industry to “drive a safety culture that is based on continuous improvement.”

For Giglio Mayor Sergio Ortelli, the memories of that night run the gamut: the horror of seeing the capsized ship, the scramble to coordinate rescue services on shore, the recovery of the first bodies and then the pride that islanders rose to the occasion to tend to the survivors.

Ortelli was later on hand when, in September 2013, the 115,000-ton, 1,000-foot long cruise ship was righted vertical off its seabed graveyard in an extraordinary feat of engineering. But the night of the disaster, a Friday the 13th, remains seared in his memory.

“It was a night that, in addition to being a tragedy, had a beautiful side because the response of the people was a spontaneous gesture that was appreciated around the world,” Ortelli said.

It seemed the natural thing to do at the time. “But then we realized that on that night, in just a few hours, we did something incredible.”

More to Read

Titanic expedition yields image of lost bronze statue, 2 million high-resolution photos

Sept. 2, 2024

Body of British tech magnate Mike Lynch is among those recovered from yacht wreckage, officials say

Aug. 22, 2024

Divers find 4 bodies during search of superyacht wreckage after it sank off Sicily, 2 more remain

Aug. 21, 2024

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

World & Nation

Blinken wraps up Ukraine-focused Europe trip in Poland with arms requests on the table

Judge tosses some counts in Georgia election case against Trump and others

Trump refuses to debate Harris again, claiming he won their first showdown

Father of Turkish American activist wants U.S. probe into her killing by Israeli soldiers

Sept. 12, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How the Wreck of a Cruise Liner Changed an Italian Island

Ten years ago the Costa Concordia ran aground off the Tuscan island of Giglio, killing 32 people and entwining the lives of others forever.

By Gaia Pianigiani

GIGLIO PORTO, Italy — The curvy granite rocks of the Tuscan island of Giglio lay bare in the winter sun, no longer hidden by the ominous, stricken cruise liner that ran aground in the turquoise waters of this marine sanctuary ten years ago.

Few of the 500-odd residents of the fishermen’s village will ever forget the freezing night of Jan. 13, 2012, when the Costa Concordia shipwrecked, killing 32 people and upending life on the island for years.

“Every one of us here has a tragic memory from then,” said Mario Pellegrini, 59, who was deputy mayor in 2012 and was the first civilian to climb onto the cruise ship after it struck the rocks near the lighthouses at the port entrance.

The hospitality of the tight-knit community of islanders kicked in, at first to give basic assistance to the 4,229 passengers and crew members who had to be evacuated from a listing vessel as high as a skyscraper. In no time, Giglio residents hosted thousands of journalists, law enforcement officers and rescue experts who descended on the port. In the months to come, salvage teams set up camp in the picturesque harbor to work on safely removing the ship, an operation that took more than two years to complete.

The people of Giglio felt like a family for those who spent long days at its port, waiting to receive word of their loved ones whose bodies remained trapped on the ship. On Thursday, 10 years to the day of the tragedy, the victims’ families, some passengers and Italian authorities attended a remembrance Mass and threw a crown of flowers onto the waters where the Costa Concordia had rested. At 9:45 p.m., the time when the ship ran aground, a candlelit procession illuminated the port’s quay while church bells rang and ship sirens blared.

What stands out now for many is how the wreck forever changed the lives of some of those whose paths crossed as a result. Friendships were made, business relations took shape and new families were even formed.

“It feels as if, since that tragic night, the lives of all the people involved were forever connected by an invisible thread,” Luana Gervasi, the niece of one of the shipwreck victims, said at the Mass on Thursday, her voice breaking.

Francesco Dietrich, 48, from the eastern city of Ancona, arrived on the island in February 2013 to work with the wreck divers, “a dream job,” he said, adding: “It was like offering someone who plays soccer for the parish team to join the Champions League with all the top teams in the business.”

For his work, Mr. Dietrich had to buy a lot of boat-repair supplies from the only hardware store in town. It was owned by a local family, and Mr. Dietrich now has a 6-year-old son, Pietro, with the family’s daughter.

“It was such a shock for us,” said Bruna Danei, 42, who until 2018 worked as a secretary for the consortium that salvaged the wreck. “The work on the Costa Concordia was a life-changing experience for me in many ways.”

A rendering of the Costa Concordia used by salvage teams to plan its recovery hung on the wall of the living room where her 22-month-old daughter, Arianna, played.

“She wouldn’t be here if Davide hadn’t come to work on the site,” Ms. Danei said, referring to Davide Cedioli, 52, an experienced diver from Turin who came to the island in May 2012 to help right the Costa Concordia — and who is also Arianna’s father.

From a barge, Mr. Cedioli monitored the unprecedented salvage operation that, in less than a day, was able to rotate the 951-foot vessel, partly smashed against the rocks, from the sea bottom to an upright position without further endangering the underwater ecosystem that it damaged when it ran aground.

“We jumped up and down in happiness when the parbuckling was completed,” Mr. Cedioli remembered. “We felt we were bringing some justice to this story. And I loved this small community and living on the island.”

The local council voted to make Jan. 13 a day of remembrance on Giglio, but after this year it will stop the public commemorations and “make it a more intimate moment, without the media,” Mr. Ortelli said during the mass.

“Being here ten years later brings back a lot of emotions,” said Kevin Rebello, 47, whose older brother, Russell, was a waiter on the Costa Concordia.

Russell Rebello’s remains were finally retrieved three years after the shipwreck, from under the furniture in a cabin, once the vessel was upright and being taken apart in Genoa.

“First, I feel close to my brother here,” Kevin Rebello said. “But it is also some sort of family reunion for me — I couldn’t wait to see the Giglio people.”

Mr. Rebello hugged and greeted residents on the streets of the port area, and recalled how the people there had shown affection for him at the time, buying him coffee and simply showing respect for his grief.

“Other victims’ families feel differently, but I am a Catholic and I have forgiven,” Mr. Rebello explained.

The Costa Concordia accident caused national shame when it became clear that the liner’s commander, Francesco Schettino, failed to immediately sound the general alarm and coordinate the evacuation, and instead abandoned the sinking vessel.

“Get back on board!” a Coast Guard officer shouted at Mr. Schettino when he understood that the captain was in a lifeboat watching people scramble to escape, audio recordings of their exchange later revealed. “Go up on the bow of the ship on a rope ladder, and tell me what you can do, how many people are there and what they need. Now!”

The officer has since pursued a successful career in politics, while Mr. Schettino is serving a 16-year sentence in a Roman prison for homicide and for abandoning the ship before the evacuation was completed. Other officials and crew members plea-bargained for lesser sentences.

During the trial, Mr. Schettino admitted that he had committed an “imprudence” when he decided to sail near the island of Giglio at high speed to greet the family of the ship’s headwaiter. The impact with the half-submerged rock near the island produced a gash in the hull more than 70 meters long, or about 76 yards, leading to blackouts on board and water pouring into the lower decks.

Mr. Schettino tried to steer the cruise ship toward the port to make evacuation easier, but the vessel was out of control and began to tip as it neared the harbor, making many lifeboats useless.

“I can’t forget the eyes of children, scared to death, and of their parents,” said Mr. Pellegrini, who had boarded the ship to speak with officials and organize the evacuation. “The metallic sound of the enormous ship tipping over and the gurgling of the sea up the endless corridors of the cruiser.”

Sergio Ortelli, who is still the mayor of Giglio ten years later, was similarly moved. “Nobody can go back and cancel those senseless deaths of innocent people, or the grief of their families,” he said. “The tragedy will always stay with us as a community. It was an apocalypse for us.”

Yet Mr. Ortelli said that the accident also told a different story, that of the skilled rescuers who managed to save thousands of lives, and of the engineers who righted the liner, refloated it and took it to the scrapyard.

While the global attention shifted away from Giglio, residents have stayed in touch with the outside world through the people who temporarily lived there.

For months, the Rev. Lorenzo Pasquotti, who was then a pastor in Giglio, kept receiving packages: dry-cleaned slippers, sweaters and tablecloths that were given to the cold, stranded passengers in his church that night, returned via courier.

One summer, Father Pasquotti ate German cookies with a German couple who were passengers on the ship. They still remembered the hot tea and leftovers from Christmas delicacies that they were given that night.

“So many nationalities — the world was at our door all of a sudden,” he said, remembering that night. “And we naturally opened it.”

Gaia Pianigiani is a reporter based in Italy for The New York Times. More about Gaia Pianigiani

Come Sail Away

Love them or hate them, cruises can provide a unique perspective on travel..

Solo Cruising: As the travel trend becomes more popular, pricing and cabin types are changing. Deals can be found, especially with advance planning, but it takes a little know-how .

Icon Class Ships: Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas has been a hit among cruise goers. The cruise line is adding to its fleet of megaships , but they have drawn criticism from environmental groups.

Cruise Ship Surprises: Here are five unexpected features on ships , some of which you hopefully won’t discover on your own.

Icon of the Seas: Our reporter joined thousands of passengers on the inaugural sailing of Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas . The most surprising thing she found? Some actual peace and quiet .

Th ree-Year Cruise, Unraveled: The Life at Sea cruise was supposed to be the ultimate bucket-list experience : 382 port calls over 1,095 days. Here’s why those who signed up are seeking fraud charges instead.

TikTok’s Favorite New ‘Reality Show’: People on social media have turned the unwitting passengers of a nine-month world cruise into “cast members” overnight.

Looking Back: Ten Years After Costa Concordia

Orlando Martinez

- January 14, 2022

Ten years ago on January 13, 2012, Costa Concordia ran aground and capsized on the rocks of Giglio, Italy.

By sunrise the next morning, 32 passengers and crew had lost their lives, and the ship’s master, Francesco Schettino, faced not only questions about what happened but accusations that he abandoned command of the ship while passengers were still in danger.

In the coming years, new safety procedures would be introduced across the cruise industry as a result of that night’s tragedy.

Let’s look back at the events of that fateful and deadly Friday the 13th and their aftermath a decade later..

How did Costa Concordia Sink?

The Costa Concordia left Civitavecchia, Italy at 7 pm local time on a seven-night cruise bound for Savona. About two and a half hours into the voyage, the ship’s Captain, Francesco Schettino, ordered the ship to leave its intended course and head toward the small island of Giglio, Italy to perform what’s known as a “sail-by salute,” a maneuver intended to impress both passengers and local residents by sailing very close to the island.

At 9:45 pm, as the ship sailed perilously close to Giglio, the port side of the ship scraped a rock, breaching the ship’s hull and causing it to lurch violently and be plunged into darkness. The ship’s officers initially only communicated news of the power outage to passengers and the Italian Coast Guard, and assured both that the situation was under control.

Meanwhile, on the bridge and below decks, chaos ensued as officers and crew members tried desperately to contain flooding that ultimately impacted the engine room. A 167-foot-long opening was torn in the hull, and three of the ship’s watertight compartments were breached — a situation that would ultimately doom the vessel.

Over the ensuing hour, Concordia was free-floating, picked up the wind and tides. The ship was blown further north, and spun around, with the starboard side coming to rest against an underwater rock shelf, which caused the ship to lurch again and begin to roll over on its side.

At about 10:42 pm, Captain Schettino finally called a General Alarm, and a short while later, lifeboats were launched as passengers and crew started abandoning ship in what has been described as a chaotic process. The ship’s increasing list led to difficulty launching lifeboats and placed a large number of the life craft inaccessible or already submerged and unable to be launched.

MORE: 9 Cruise Line Private Islands and Where They Are Located

Timeline of Costa Concordia Sinking

Over 90 minutes after the first impact with the rocky island shore, Italian Coast Guard rescue teams begin to arrive.

Frustrated by unsuccessful efforts to reach Captain Schettino by radio, Gregorio De Falco, commander of the Livorno coast guard fleet, calls Schettino on his cell phone and is shocked to hear the Captain is on a lifeboat.

Here’s a partial transcript of one of their blistering conversations:

De Flaco: What are you doing Captain?

Schettino: I am here going with the lifeboat. I am here coordinating rescues.

DF: What are you coordinating from there? Schettino? Listen to me Schettino. There are people trapped on board. Now, you go with your lifeboat back on the ship… you tell me how many people there are. Is that clear? … You tell me if there are children, women, or people in need of assistance and tell me the number in each of these categories.

S: Commander, please.

DF: Are you refusing to go back on board, Captain? Tell me the reason why you are not going.

S: Do you realize it’s dark here and we can’t see anything

DF: What, do you want to go home, Schettino? It’s dark so you want to go home? Go back on the ship through the ladder and tell me what we can do. How many people there are and what do they need? Now! Schettino you might have saved yourself from the sea, but this is really bad. I’ll make you go through hell. Go the f – – k on board!

The Captain defied the order.

By 1 am, the last functional lifeboat pulled away from the ship, leaving over 100 still on board to be rescued by Coast Guard divers and choppers, and, later, by walking down a ladder on the side of the ship, holding hands.

The port side of the ship was nearly horizontal at that point, with some passengers climbing and clinging to the hull awaiting evacuation. The Coast Guard knew that people were falling, jumping or being pushed into the frigid water, an all but certain death sentence for those not able to be rescued or reach shore quickly.

Those lucky enough to make it off the ship were welcomed with open arms by Giglio’s residents who offered warn blankets, food and water, and accommodation in their homes.

As daylight broke, a massive search and rescue operation for about 100 missing passengers and crew grew larger. A week later, 20 people are still unaccounted for, with 12 confirmed to be dead, foreshadowing the final death toll of 32.

The body of one crew member was not recovered until after the ship was salvaged and being scrapped, over two and a half years later.

Schettino’s Fate

In the days following the tragedy, Captain Schettino was placed under house arrest, charged with manslaughter, abandoning the ship, and causing a shipwreck.

Rumors that the married 51-year-old Captain was entertaining a young, alleged mistress on the bridge, Moldovan dancer Domnica Cemortan, when the ship ran aground, took over the tabloid newspapers and Twitter.

Reports indicated the young woman was sailing as a guest of the captain and was not on passenger manifests. When audiotapes of Schettino’s conversation with De Falco of the Coast Guard were released, public sentiment in Italy turned further against the Captain.

In July 2013, Schettino’s trial began and was under intense media scrutiny. A key question at trial was who ordered the ship to sail close to Giglio: was it Costa Cruises leadership, or did the ‘rogue’ Captain Schettino make the call?

During testimony, Schettino admitted he did not inform the company of the deviation from the ship’s course, as it was not an official order.

Facing charges of abandoning the ship, Schettino claimed during the trial that he tripped and fell into a lifeboat and was forced to leave the ship. Video of him entering the lifeboat leisurely contradicts his assertion.

Schettino’s trial lasted 19 months, and he was ultimately sentenced to 16 years and one month of prison time. His appeal was not successful.

Five other crew members who had a role in the sail-by or who otherwise did not take appropriate action to prevent the tragedy took plea bargains for manslaughter but ultimately avoided prison time.

MORE: 18 New Cruise Ships Debuting in 2022

The Cruise Industry Refocuses on Safety

In the aftermath of Costa Concordia, both regulators and major players in the cruise industry revised safety guidelines within months, aiming to prevent a similar incident in the future.

Among the first changes implemented was making the muster drill mandatory for all passengers prior to the ship setting sail. Previously, passengers could muster up to 24 hours after boarding, which means some passengers who boarded Concordia in Civitavecchia on January 13 may not have completed their drill, meaning they did not know what to do or where to report in the event of an emergency.

In Italy, government officials instituted a “no salute” decree shortly after the incident, impacting navigation procedures in and around Venice.

Shipbuilders and cruise lines have made changes in ship design and operation to better accommodate evacuations under different contingencies.

Around the world, ports have assessed their ability to respond to a large-scale, mass-casualty like the Costa Concordia grounding and are better prepared in the event of an emergency.

Though cruise bookings dropped in the immediate aftermath of the Costa Concordia tragedy, they quickly recovered as images of the grounded ship faded from TV screens and newspaper pages.

READ NEXT: 11 Former Carnival Ships – Where Are They Now?

- Norwegian Gem Set to Launch Cruises from Jacksonville in 2025

- Tender Issues Cause NCL Cruise Ships to Skip Venice

- The First Cruise Line in History Will Homeport in Washington, D.C.

- Carnival Expects Revenue Hit by Scraping Red Sea Transits on 12 Ships

Recent Posts

- Lee Mason Promoted to Fleet Cruise Director, Leaving Carnival Venezia

- Carnival Cruise Ship Held at Sea Until New Orleans Port Reopens

- Hurricane Francine Keeps Carnival Cruise Ship at Sea

- Carnival and Disney Shipyard Secures Bailout to Stay Afloat

Bringing you 15 years of cruise industry experience. Cruise Radio prioritizes well-balanced cruise news coverage and accurate reporting, paired with ship reviews and tips.

Quick links

Cruise Radio, LLC © Copyright 2009-2024 | Website Designed By Insider Perks, Inc

Costa Concordia: Ten years on pianist recalls terrifying escape from the capsized cruise liner

Ten years on from the tragedy, Antimo Magnotta has revealed how he still has "terrible flashbacks" and can remember people's screams as the enormous vessel tipped over off the coast of Italy.

Thursday 13 January 2022 17:06, UK

On 13 January 2012, the Italian cruise ship Costa Concordia capsized off the coast of Tuscany after hitting a rock in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Francesco Schettino, the captain of the cruise liner, was jailed for 16 years for multiple manslaughter after the disaster that left 32 people dead.

On the tenth anniversary of the tragedy, the ship's Italian pianist Antimo Magnotta, who is now living and working in London, has relived his terrifying ordeal and told Sky News how he is still tormented by flashbacks from what he witnessed.

I was working in a very elegant bar at the back of the ship called Bar Vienna. I remember it was a beautiful night, a starry night, the sea was very calm and quiet.

Then all of a sudden the ship suddenly swerved and started tilting. It was really unexpected because the conditions at sea meant it made no sense for this to happen.

I thought to myself - "did we hit a whale or a giant monster or something?".

I fell over and the piano started drifting on stage. I left the bar and found myself stumbling along sloping corridors with passengers and crew members. I was heading to the centre of the ship where there would be more balance.

More from World

Long-range missile approval will put NATO - including UK and US - 'at war' with Russia, Putin warns

SpaceX Polaris Dawn: Billionaire Jared Isaacman becomes first person to take part in private spacewalk

US election latest: Trump speaks at first rally since debate, as he rules out another - but Harris says 'we owe it to voters'

When I got there I found myself with other crew members and passengers on this huge dancefloor. We were expecting some instructions, some kind of explanation, but the ship began to have multiple blackouts and power failures.

The ship was performing some very strange movements, it was tilting on one side and then slowly titling on the other side, I was thinking to myself - "what is this?".

Passengers and crew members were screaming and calling out names. We couldn't see each other in the darkness.

It was quite cinematic I must say, it looked like a David Lynch film actually.

Finally, after more than an hour, the emergency signal on board was sounded.

I was a pianist, but I was also a crew member, and I had been trained to carrying out certain duties in an emergency.

I reached my master station and was in charge of a roll call for 25 crew members to embark on a life raft. I remember four people on my list were missing.

I was expecting a crew member from the bridge (the room where the ship is commanded) to come downstairs and lead myself and my crew members to our designated life raft.

But no one came from the bridge, and of course the ship, in the meantime, was still performing this very macabre choreography of slowly capsizing.

While the ship was tipping over I was confronted with a portrait of an ongoing tragedy, a grotesque paradox.

It was like being inside a cabinet of horrors. I mainly remember the sounds - there was this cacophony from the bowels of the ship. People were screaming.

I describe the ship in this moment as being like a swan in agony. It was suffering.

I eventually saw a crew member dressed all in white carrying a box of walkie talkies. I asked him what was going on.

He whispered: "Don't you know? We hit a rock, and this caused a massive leak on the side of the ship."

He was very agitated, he was running on adrenaline, and said: "You know what, the best suggestion would be for you to run for your life, and if you can, abandon the ship."

I thought this must be some kind of joke, but then he just vanished.

Everyone was really panicking and end up scattering all around.

This was the very beginning of my personal nightmare, because I had to perform a gruelling evacuation of the ship.

I knew where the life raft I was supposed to get on was located, and I knew it would now be under water.

I was 41 at the time and said to myself I can't die, this must be a joke.

But I started thinking about my daughter and this triggered a reaction in me, so I started climbing on some metallic bars, some ladders, pipes, whatever I could find in my way.

It took some time, but I found myself on the flank of the ship outside, facing the dark sea, holding onto a winch, a crane, I was holding on to this rope like I was clinging on to life itself.

All I had to do was just wait to be rescued, It was difficult because it was pitch dark, the most difficult thing to do was to make myself visible.

This lasted pretty much four hours.

The ship was more or less on it side by this point, breaching at a very dramatic angle, maybe 80 to 85 degrees, if not more.

It was like the carcass of a stranded whale. I could feel and hear the death rattle of the ship.

When I was on the flank of the ship I felt something is deteriorating, disintegrating, my image, my story, was fading away, it was vanishing, "I can't die," I said to myself.

I was not alone of course, there was a bunch of between 35 to 40 people around me, passengers and crew members.

I could see rescue boats and there was very frantic activity in the water. Helicopters were hovering above but they didn't seem to see us.

Eventually a little rescue boat was sent for us, and I will always say, jumping in this little rescue boat was like jumping back to life.

It was 3am, more than five hours after the ship hit the rock, that the rescue boat dropped me off at Giglio Island.

It was like celebrating a second birthday, it was the beginning of my second life.

Unfortunately, later on, I learned that two fellow musicians had lost their lives. My friend, a Hungarian violinist, who lost his life, had just gone down to his cabin.

I just thought to myself what if it had been the other way round?

This has haunted me for a long time.

In the aftermath of the disaster I was devastated and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

I had mental scars still lingering, survivor's guilt and chronic insomnia. I couldn't play the piano anymore. I had a stone in my chest and not a heart.

I took up a new form of self-therapy and started writing, and I would cry sometimes of course.

It was a way to express myself and my anger.

These days I feel much better and I play the piano in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Now I am feeling much better, but still I have terrible flashbacks and insomnia - my sleep is always interrupted.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

Another Night to Remember

At the Italian port of Civitavecchia, 40 miles northwest of Rome, the great cruise ships line the long concrete breakwater like taxis at a curb. That Friday afternoon, January 13, 2012, the largest and grandest was the Costa Concordia, 17 decks high, a floating pleasure palace the length of three football fields. It was a cool, bright day as the crowds filed on and off the ship, those who had boarded at Barcelona and Marseilles heading into Rome for sightseeing while hundreds of new passengers pulled rolling bags toward the *Concordia’*s arrival terminal.

Up on the road, a writer from Rome named Patrizia Perilli stepped from a chauffeur-driven Mercedes and marveled at the ship’s immensity. “You could see it even before you entered the port; it was a floating monster,” she recalls. “Its size made me feel secure. It was sunny, and its windows were just sparkling.”

Inside the terminal, newcomers handed their luggage to the Indian and Filipino pursers. There was a welcome desk for an Italian reality show, Professione LookMaker, filming on board that week; among those arriving were 200 or so hairdressers from Naples and Bologna and Milan, all hoping to make it onto the show. As they chattered, flashed their passports, and boarded, then slowly filtered throughout the ship, they thought it all grand: 1,500 luxury cabins, six restaurants, 13 bars, the two-story Samsara Spa and fitness center, the three-story Atene Theatre, four swimming pools, the Barcellona Casino, the Lisbona Disco, even an Internet café, all wrapped around a dramatic, nine-story central atrium, itself a riot of pink, blue, and green lights.

Some of the hundred or so Americans on board weren’t so wowed. One likened wandering the Concordia to getting lost inside a pinball machine. “It kind of reminded me of old Vegas, you know?” says Benji Smith, a 34-year-old Massachusetts honeymooner, who had boarded at Barcelona with his wife, along with two of her relatives and two of their friends, all from Hong Kong. “Everything was really gaudy, lots of fancy blown glass in different colors. The entertainment kind of reinforced the old-Vegas thing, aging singers performing solo on a keyboard with a drum track.”

There were just over 4,200 people aboard the Concordia as it eased away from the breakwater that evening, about a thousand crew members and 3,200 passengers, including nearly a thousand Italians, hundreds of French, British, Russians, and Germans, even a few dozen from Argentina and Peru. Up on Deck 10, Patrizia Perilli stepped onto her balcony and daydreamed about sunbathing. As she began to unpack in her elegant stateroom, she glanced over at her boyfriend, who was watching a video on what to do if they needed to abandon ship. Perilli teased him, “What would we ever need that for?”

As the world now knows, they needed it desperately. Six hours later the Concordia would be lying on its side in the sea, freezing water surging up the same carpeted hallways that hairdressers and newlyweds were already using to head to dinner. Of the 4,200 people on board, 32 would be dead by dawn.

The wreck of the Costa Concordia is many things to many people. To Italians, who dominated the ship’s officer ranks and made up a third of its passengers, it is a national embarrassment; once the pinnacle of Mediterranean hedonism, the Concordia was now sprawled dead on the rocks in a cold winter sea.

But the *Concordia’*s loss is also a landmark moment in naval history. It is the largest passenger ship ever wrecked. The 4,000 people who fled its slippery decks—nearly twice as many as were aboard the R.M.S. Titanic in 1912—represent the largest maritime evacuation in history. A story of heroism and disgrace, it is also, in the mistakes of its captain and certain officers, a tale of monumental human folly.

“This was an episode of historic importance for those who study nautical issues,” says Ilarione Dell’Anna, the Italian Coast Guard admiral who oversaw much of the massive rescue effort that night. “The old point of departure was the Titanic. I believe that today the new point of departure will be the Costa Concordia. There has never been anything like this before. We must study this, to see what happened and to see what we can learn.”

Much of what happened on the night of January 13 can now be told, based on the accounts of dozens of passengers, crew members, and rescue workers. But the one group whose actions are crucial to any understanding of what went wrong—the ship’s officers—has been largely mute, silenced first by superiors at Costa Cruises and now by a web of official investigations. The officers have spoken mainly to the authorities, but this being the Italian justice system, their stories quickly leaked to the newspapers—and not simply, as happens in America, via the utterances of anonymous government officials. In Rome entire transcripts of these interrogations and depositions have been leaked, affording a fairly detailed, if still incomplete, portrait of what the captain and senior officers say actually happened.

Captain, My Captain

The Concordia first sailed into the Tyrrhenian Sea, from a Genoese shipyard, in 2005; at the time it was Italy’s largest cruise ship. When it was christened, the champagne bottle had failed to break, an ominous portent to superstitious mariners. Still, the ship proved a success for its Italian owner, Costa Cruises, a unit of the Miami-based Carnival Corporation. The ship sailed only in the Mediterranean, typically taking a circular route from Civitavecchia to Savona, Marseilles, Barcelona, Majorca, Sardinia, and Sicily.

In command on the bridge that night was 51-year-old Captain Francesco Schettino, today a figure of international contempt. Dashing and deeply tanned, with lustrous black hair, Schettino had joined Costa as a safety officer in 2002, been promoted to captain in 2006, and since September had been on his second tour aboard the Concordia. Among the officers, he was respected, though the retired captain who had mentored him later told prosecutors he was a bit too “exuberant” for his own good. Despite being married, Schettino had a lady friend at his side that evening, a comely 25-year-old off-duty hostess named Domnica Cemortan, from Moldova. Though she would later become an object of intense fascination in the press, Cemortan’s role in events that night was inconsequential.

Before leaving port, Captain Schettino set a course for Savona, on the Italian Riviera, 250 miles to the northwest. As the ship steamed into the Tyrrhenian, Schettino headed to dinner with Cemortan, telling an officer to alert him when the Concordia closed within five miles of the island of Giglio, 45 miles northwest. Later, a passenger would claim he saw Schettino and his friend polish off a decanter of red wine while eating, but the story was never confirmed. Around nine Schettino rose and, with Cemortan in tow, returned to the bridge.

Ahead lay mountainous Giglio, a collection of sleepy villages and vacation homes clustered around a tiny stone harbor, nine miles off the coast of Tuscany.

The *Concordia’*s normal course took it through the middle of the channel between Giglio and the mainland, but as Schettino arrived, it was already veering toward the island. The ship’s chief maître d’, Antonello Tievoli, was a native of Giglio and had asked the captain to perform a “salute,” essentially a slow drive-by, a common cruise-industry practice intended to show off the ship and impress local residents. Schettino had consented, in part because his mentor, Mario Palombo, lived there, too. Palombo had performed several salutes to Giglio, Schettino at least one.

As the ship made its approach, Tievoli, standing on the bridge, placed a telephone call to Palombo. The retired captain, it turned out, wasn’t on Giglio; he was at a second home, on the mainland. After some chitchat, Tievoli handed the telephone to the captain, which, Palombo told prosecutors, caught him off guard. He and Schettino hadn’t talked in at least seven years; Schettino hadn’t bothered to call when Palombo retired. “The call surprised me,” Palombo said. “I was even more surprised when Schettino asked me about the depth of the seabed in front of Giglio Island, the harbor area, specifying that he wanted to pass at a distance of 0.4 nautical miles [around 800 yards]. I answered that in that area the seabeds are good, but considering the winter season”—when few people were on the island—“there was no reason to go at close range, so I invited him to make a quick greeting and to honk the horn and remain far from shore. I want to clarify that I said, verbatim, ‘Say hi and stay away.’ ”

Just then the phone went dead. It may have been the very moment Schettino saw the rock.

Not until the ship had closed within two miles of the island, Schettino’s officers told prosecutors, did the captain take personal control of the ship. As Schettino recalled it, he stood at a radar station, in front of the broad outer windows, affording him a clear view of Giglio’s lights. An Indonesian crewman, Rusli Bin Jacob, remained at the helm, taking orders from the captain. The maneuver Schettino planned was simple, one he had overseen many, many times, just an easy turn to starboard, to the right, that would take the Concordia parallel to the coastline, dazzling the island’s residents with the length of the fully lit ship as it slid past. In doing so, however, Schettino made five crucial mistakes, the last two fatal. For one thing, the Concordia was going too fast, 15 knots, a high speed for maneuvering so close to shore. And while he had consulted radar and maps, Schettino seems to have been navigating largely by his own eyesight—“a major mistake,” in one analyst’s words. His third error was the bane of every American motorist: Schettino was talking on the phone while driving.

Schettino’s fourth mistake, however, appears to have been an amazingly stupid bit of confusion. He began his turn by calculating the distance from a set of rocks that lay about 900 yards off the harbor. What he failed to notice was another rock, nearer the ship. Giving orders to Bin Jacob, Schettino eased the Concordia into the turn without event. Then, coming onto a new, northerly course just over a half-mile from the harbor, he saw the rock below, to his left. It was enormous, just at the surface, crowned with frothing white water; he was so close to Giglio he could see it by the town’s lights.

He couldn’t believe it.

“Hard to starboard!” Schettino yelled.

It was an instinctive order, intended to steer the ship away from the rock. For a fleeting moment Schettino thought it had worked. The *Concordia’*s bow cleared the rock. Its midsection cleared as well. But by turning the ship to starboard the stern swung toward the island, striking the submerged part of the rock. “The problem was that I went to starboard trying to avoid it, and that was the mistake, because I should not have gone starboard,” Schettino told prosecutors. “I made an imprudent decision. Nothing would have happened if I had not set the helm to starboard.”

“Hard to port!” Schettino commanded, correcting his mistake.

A moment later, he shouted, “Hard to starboard!”

And then the lights went out.

It was 9:42. Many of the passengers were at dinner, hundreds of them in the vast Milano Restaurant alone. A Schenectady, New York, couple, Brian Aho and Joan Fleser, along with their 18-year-old daughter, Alana, had just been served eggplant-and-feta appetizers when Aho felt the ship shudder.

“Joan and I looked at each other and simultaneously said, ‘That’s not normal,’ ” recalls Aho. “Then there was a bang bang bang bang . Then there was just a great big groaning sound.”

“I immediately felt the ship list severely to port,” Fleser says. “Dishes went flying. Waiters went flying all over. Glasses were flying. Exactly like the scene in Titanic. ”

“I took the first bite of my eggplant and feta,” Aho says, “and I literally had to chase the plate across the table.”

“Suddenly there was a loud bang,” recalls Patrizia Perilli. “It was clear there had been a crash. Immediately after that there was a very long and powerful vibration—it seemed like an earthquake.”

A Bologna hairdresser, Donatella Landini, was sitting nearby, marveling at the coastline, when she felt the jolt. “The sensation was like a wave,” she recalls. “Then there was this really loud sound like a ta-ta-ta as the rocks penetrated the ship.” Gianmaria Michelino, a hairdresser from Naples, says, “The tables, plates, and glasses began to fall and people began to run. Many people fell. Women who had been running in high heels fell.”

All around, diners surged toward the restaurant’s main entrance. Aho and Fleser took their daughter and headed for a side exit, where the only crew member they saw, a sequined dancer, was gesticulating madly and shouting in Italian. “Just as we were leaving, the lights went out,” Fleser says, “and people started screaming, really panicking. The lights were out only for a few moments; then the emergency lights came on. We knew the lifeboats were on Deck 4. We didn’t even go back to our room. We just went for the boats.”

“We stayed at our table,” recalls Perilli. “The restaurant emptied and there was a surreal silence in the room. Everyone was gone.”

Somewhere on the ship, an Italian woman named Concetta Robi took out her cell phone and dialed her daughter in the central Italian town of Prato, near Florence. She described scenes of chaos, ceiling panels falling, waiters stumbling, passengers scrambling to put on life jackets. The daughter telephoned the police, the carabinieri.

As passengers tried in vain to understand what was happening, Captain Schettino stood on the bridge, stunned. An officer nearby later told investigators he heard the captain say, “Fuck. I didn’t see it!”

In those first confusing minutes, Schettino spoke several times with engineers belowdecks and sent at least one officer to assess the damage. Moments after the Concordia struck the rock, the chief engineer, Giuseppe Pilon, had hustled toward his control room. An officer emerged from the engine room itself shouting, “There’s water! There’s water!” “I told him to check that all the watertight doors were closed as they should be,” Pilon told prosecutors. “Just as I finished speaking we had a total blackout I opened the door to the engine room and the water had already risen to the main switchboard I informed Captain Schettino of the situation. I told him that the engine room, the main switchboard, and the stern section were flooded. I told him we had lost control of the ship.”

There was a 230-foot-long horizontal gash below the waterline. Seawater was exploding into the engine room and was fast cascading through areas holding all the ship’s engines and generators. The lower decks are divided into giant compartments; if four flood, the ship will sink.

At 9:57, 15 minutes after the ship struck the rock, Schettino phoned Costa Cruises’ operations center. The executive he spoke to, Roberto Ferrarini, later told reporters, “Schettino told me there was one compartment flooded, the compartment with electrical propulsion motors, and with that kind of situation the ship’s buoyancy was not compromised. His voice was quite clear and calm.” Between 10:06 and 10:26, the two men spoke three more times. At one point, Schettino admitted that a second compartment had flooded. That was, to put it mildly, an understatement. In fact, five compartments were flooding; the situation was hopeless. (Later, Schettino would deny that he had attempted to mislead either his superiors or anyone else.)

They were sinking. How much time they had, no one knew. Schettino had few options. The engines were dead. Computer screens had gone black. The ship was drifting and losing speed. Its momentum had carried it north along the island’s coastline, past the harbor, then past a rocky peninsula called Point Gabbianara. By 10 P.M., 20 minutes after striking the rock, the ship was heading away from the island, into open water. If something wasn’t done immediately, it would sink there.

What happened next won’t be fully understood until the *Concordia’*s black-box recorders are analyzed. But from what little Schettino and Costa officials have said, it appears that Schettino realized he had to ground the ship; evacuating a beached ship would be far safer than evacuating at sea. The nearest land, however, was already behind the ship, at Point Gabbianara. Somehow Schettino had to turn the powerless Concordia completely around and ram it into the rocks lining the peninsula. How this happened is not clear. From the ship’s course, some analysts initially speculated that Schettino used an emergency generator to gain control of the ship’s bow thrusters—tiny jets of water used in docking—which allowed him to make the turn. Others maintain that he did nothing, that the turnabout was a moment of incredible luck. They argue that the prevailing wind and current—both pushing the Concordia back toward the island—did most of the work.

“The bow thrusters wouldn’t have been usable, but from what we know, it seems like he could still steer,” says John Konrad, a veteran American captain and nautical analyst. “It looks like he was able to steer into the hairpin turn, and wind and current did the rest.”

However it was done, the Concordia completed a hairpin turn to starboard, turning the ship completely around. At that point, it began drifting straight toward the rocks.

I larione Dell’Anna, the dapper admiral in charge of Coast Guard rescue operations in Livorno, meets me on a freezing evening outside a columned seaside mansion in the coastal city of La Spezia. Inside, waiters in white waistcoats are busy laying out long tables lined with antipasti and flutes of champagne for a naval officers’ reception. Dell’Anna, wearing a blue dress uniform with a star on each lapel, takes a seat on a corner sofa.

“I’ll tell you how it all started: It was a dark and stormy night,” he begins, then smiles. “No, seriously, it was a quiet night. I was in Rome. We got a call from a town outside Florence. The party, a carabinieri officer, had a call from a woman whose mother was on a ship, we don’t know where, who was putting on life jackets. Very unusual, needless to say, for us to get such a call from land. Ordinarily a ship calls us. In this case, we had to find the ship. We were the ones who triggered the entire operation.”

That first call, like hundreds of others in the coming hours, arrived at the Coast Guard’s rescue-coordination center, a cluster of red-brick buildings on the harbor in Livorno, about 90 miles north of Giglio. Three officers were on duty that night inside its small operations room, a 12-by-25-foot white box lined with computer screens. “At 2206, I received the call,” remembers one of the night’s unsung heroes, an energetic 37-year-old petty officer named Alessandro Tosi. The carabinieri “thought it was a ship going from Savona to Barcelona. I called Savona. They said no, no ship had left from there. I asked the carabinieri for more information. They called the passenger’s daughter, and she said it was the Costa Concordia. ”

Six minutes after that first call, at 10:12, Tosi located the Concordia on a radar screen just off Giglio. “So then we called the ship by radio, to ask if there was a problem,” Tosi recalls. An officer on the bridge answered. “He said it was just an electrical blackout,” Tosi continues. “I said, ‘But I’ve heard plates are falling off the dinner tables—why would that be? Why have passengers been ordered to put on life jackets?’ And he said, ‘No, it’s just a blackout.’ He said they would resolve it shortly.”

The Concordia crewman speaking with the Coast Guard was the ship’s navigation officer, a 26-year-old Italian named Simone Canessa. “The Captain ordered … Canessa to say that there was a blackout on board,” third mate Silvia Coronica later told prosecutors. “When asked if we needed assistance, he said, ‘At the moment, no.’ ” The first mate, Ciro Ambrosio, who was also on the bridge, confirmed to investigators that Schettino was fully aware that a blackout was the least of their problems. “The captain ordered us to say that everything was under control and that we were checking the damage, even though he knew that the ship was taking on water.”

Tosi put the radio down, suspicious. This wouldn’t be the first captain who downplayed his plight in hopes of avoiding public humiliation. Tosi telephoned his two superiors, both of whom arrived within a half-hour.

At 10:16, the captain of a Guardia di Finanza cutter—the equivalent of U.S. Customs—radioed Tosi to say he was off Giglio and offered to investigate. Tosi gave the go-ahead. “I got back to the [ Concordia ] and said, ‘Please keep us abreast of what is going on,’ ” says Tosi. “After about 10 minutes, they didn’t update us. Nothing. So we called them again, asking, ‘Can you please update us?’ At that point, they said they had water coming in. We asked what sort of help they needed, and how many people on board had been injured. They said there were no injured. They requested only one tugboat.” Tosi shakes his head. “One tugboat.”

Schettino’s apparent refusal to promptly admit the *Concordia’*s plight—to lie about it, according to the Coast Guard—not only was a violation of Italian maritime law but cost precious time, delaying the arrival of rescue workers by as much as 45 minutes. At 10:28 the Coast Guard center ordered every available ship in the area to head for the island of Giglio.

With the Concordia beginning to list, most of the 3,200 passengers had no clue what to do. A briefing on how to evacuate the ship wasn’t to take place until late the next day. Many, like the Aho family, streamed toward the lifeboats, which lined both sides of Deck 4, and opened lockers carrying orange life jackets. Already, some were panicking. “The life jacket I had, a woman was trying to rip it out of my arms. It actually ripped the thing—you could hear it,” Joan Fleser says. “We stayed right there by one of the lifeboats, No. 19. The whole time we were standing there I only saw one crew member walk by. I asked what was happening. He said he didn’t know. We heard two announcements, both the same, that it was an electrical problem with a generator, technicians were working on it, and everything was under control.”

Internet videos later showed crewmen exhorting passengers to return to their staterooms, which, while jarring in light of subsequent events, made sense at the time: There had been no order to abandon ship. When Addie King, a New Jersey graduate student, emerged from her room wearing a life jacket, a maintenance worker actually told her to put it away. Like most, she ignored the advice and headed to the starboard side of Deck 4, where hundreds of passengers were already lining the rails, waiting and worrying. The Massachusetts newlyweds, Benji Smith and Emily Lau, were among them. “Some people are already crying and screaming,” Smith recalls. “But most people were still pretty well collected. You could see some laughing.”

For the moment, the crowd remained calm.

The island of Giglio, for centuries a haven for vacationing Romans, has a long history of unexpected visitors. Once, they were buccaneers: in the 16th century, the legendary pirate Barbarossa carted off every person on the island to slavery. Today, Giglio’s harbor, ringed by a semicircular stone esplanade lined with cafés and snack shops, is home to a few dozen fishing boats and sailboats. In summer, when the tourists come, the population soars to 15,000. In winter barely 700 remain.

That night, on the far side of the island, a 49-year-old hotel manager, Mario Pellegrini, was pointing a remote control at his television, trying in vain to find something to watch. A handsome man with a mop of curly brown hair and sprays of wrinkles at his eyes, Pellegrini was exhausted. The day before, he and a pal had gone fishing, and when the motor on their boat died, they ended up spending the night at sea. “The sea is not for me,” he sighed to his friend afterward. “You can sell that damn boat.”

The phone rang. It was a policeman at the port. A big ship, he said, was in trouble, just outside the harbor. Pellegrini, the island’s deputy mayor, had no idea how serious the matter was, but the policeman sounded worried. He hopped in his car and began driving across the mountain toward the port, dialing others on Giglio’s island council as he went. He reached a tobacco-shop owner, Giovanni Rossi, who was at his home above the harbor watching his favorite movie, Ben-Hur. “There’s a ship in trouble out there,” Pellegrini told him. “You should get down there.”

“What do you mean, there’s a ship out there?” Rossi said, stepping to his window. Parting the curtains, he gasped. Then he threw on a coat and raced down the hill toward the port. A few moments later, Pellegrini rounded the mountainside. Far below, just a few hundred yards off Point Gabbianara, was the largest ship he had ever seen, every light ablaze, drifting straight toward the rocks alongside the peninsula.

“Oh my God,” Pellegrini breathed.

After completing its desperate hairpin turn away from the open sea, the Concordia struck ground a second time that night between 10:40 and 10:50, running onto the rocky underwater escarpment beside Point Gabbianara, facing the mouth of Giglio’s little harbor, a quarter-mile away. Its landing, such as it was, was fairly smooth; few passengers even remember a jolt. Later, Schettino would claim that this maneuver saved hundreds, maybe thousands, of lives.

In fact, according to John Konrad’s analysis, it was here that Schettino made the error that actually led to many of the deaths that night. The ship was already listing to starboard, toward the peninsula. In an attempt to prevent it from falling further—it eventually and famously flopped onto its right side—Schettino dropped the ship’s massive anchors. But photos taken later by divers show clearly that they were lying flat, with their flukes pointed upward; they never dug into the seabed, rendering them useless. What happened?

Konrad says it was a jaw-droppingly stupid mistake. “You can see they let out too much chain,” he says. “I don’t know the precise depths, but if it was 90 meters, they let out 120 meters of chain. So the anchors never caught. The ship then went in sideways, almost tripping over itself, which is why it listed. If he had dropped the anchors properly, the ship wouldn’t have listed so badly.”

What could explain so fundamental a blunder? Video of the chaos on the bridge that night later surfaced, and while it sheds little light on Schettino’s technical decisions, it says worlds about his state of mind. “From the video, you can tell he was stunned,” says Konrad. “The captain really froze. It doesn’t seem his brain was processing.”

Schettino did make efforts, however, to ensure that the ship was firmly grounded. As he told prosecutors, he left the bridge and went to Deck 9, near the top of the ship, to survey its position. He worried it was still afloat and thus still sinking; he asked for that tugboat, he said, with the thought it might push the ship onto solid ground. Eventually satisfied it already was, he finally gave the order to abandon ship at 10:58.

Lifeboats lined the railings on both sides of Deck 4. Because the Concordia was listing to starboard, it eventually became all but impossible to lower boats from the port side, the side facing open water; they would just bump against lower decks. As a result, the vast majority of those who evacuated the ship by lifeboat departed from the starboard side. Each boat was designed to hold 150 passengers. By the time Schettino called to abandon ship, roughly 2,000 people had been standing on Deck 4 for an hour or more, waiting. The moment crewmen began opening the lifeboat gates, chaos broke out.

“It was every man, woman, and child for themselves,” says Brian Aho, who crowded onto Lifeboat 19 with his wife, Joan Fleser, and their daughter.

“We had an officer in our lifeboat,” Fleser says. “That was the only thing that kept people from totally rioting. I ended up being first, then Brian and then Alana.”

“There was a man who was trying to elbow Alana out of the way,” Aho recalls, “and she pointed at me, yelling in Italian, ‘Mio papà! Mio papà!’ I saw her feet on the deck above me and I pulled her in by the ankles.”

“The thing I remember most is people’s screams. The cries of the women and children,” recalls Gianmaria Michelino, the hairdresser. “Children who couldn’t find their parents, women who wanted to find their husbands. Children were there on their own.”

Claudio Masia, a 49-year-old Italian, waiting with his wife, their two children, and his elderly parents, lost patience. “I am not ashamed to say that I pushed people and used my fists to secure a place” for his wife and children, he later told an Italian newspaper. Returning for his parents, Masia had to carry his mother, who was in her 80s, into a boat. When he returned for his father, Giovanni, an 85-year-old Sardinian, he had vanished. Masia ran up and down the deck, searching for him, but Giovanni Masia was never seen again.

‘Someone at our muster station called out, ‘Women and children first,’ ” recalls Benji Smith. “That really increased the panic level. The families who were sticking together, they’re being pulled apart. The women don’t want to go without their husbands, the husbands don’t want to lose their wives.”

After being momentarily separated from his wife, Smith pushed his way onto a lifeboat, which dangled about 60 feet above the water. Immediately, however, the crew had problems lowering it. “This is the first part where I thought my life was in danger,” Smith goes on. “The lifeboats have to be pushed out and lowered down. We weren’t being lowered down slowly and evenly from both directions. The stern side would fall suddenly by three feet, then the bow by two feet; port and starboard would tilt sharply to one side or the other. It was very jerky, very scary. The crew members were shouting at each other. They couldn’t figure out what they were doing.” Eventually, to Smith’s dismay, the crewmen simply gave up, cranked the lifeboat back up to the deck, and herded all the passengers back onto the ship.

Others, blocked or delayed in getting into lifeboats, threw themselves into the water and swam toward the rocks at Point Gabbianara, 100 yards way. One of these was a 72-year-old Argentinean judge named María Inés Lona de Avalos. Repeatedly turned away from crowded lifeboats, she sat on the deck amid the chaos. “I could feel the ship creaking, and we were already leaning halfway over,” she later told a Buenos Aires newspaper. A Spaniard beside her yelled, “There’s no other option! Let’s go!” And then he jumped.

A moment later Judge Lona, a fine swimmer in her youth, followed.

“I jumped feetfirst I couldn’t see much. I began swimming, but every 50 feet I would stop and look back. I could hear the ship creaking and was scared that it would fall on top of me if it capsized completely. I swam for a few minutes and reached the island.” She sat on a wet rock and exhaled.

A French couple, Francis and Nicole Servel, jumped as well, after Francis, who was 71, gave Nicole his life jacket because she couldn’t swim. As she struggled toward the rocks, she yelled, “Francis!,” and he replied, “Don’t worry, I’ll be fine.” Francis Servel was never seen again.

The first lifeboats limped into the harbor a few minutes after 11.

By the time Giglio’s deputy mayor, Mario Pellegrini, reached the harbor, townspeople had begun to collect on its stone esplanade. “We’re all looking at the ship, trying to figure out what happened,” he recalls. “We thought it must be an engine breakdown of some kind. Then we saw the lifeboats dropping down, and the first ones began to arrive in the port.” Local schools and the church were opened, and the first survivors were hustled inside and given blankets. Every free space began to fill.

“I looked at the mayor and said, ‘We’re such a small port—we should open the hotels,’ ” Pellegrini says. “Then I said, ‘Maybe it’s better for me to go on board to see what’s going on.’ I didn’t have a minute to think. I just jumped on a lifeboat, and before I knew it I was out on the water.”

Reaching the ship, Pellegrini grabbed a rope ladder dangling from a lower deck. “As soon as I got on board, I started looking for someone in charge. There were just crew members, standing and talking on Deck 4, with the lifeboats. They had no idea what was going on. I said, ‘I’m looking for the captain, or someone in charge. I’m the deputy mayor! Where’s the captain?’ Everyone goes, ‘I don’t know. There’s no one in charge.’ I was running around like that for 20 minutes. I ran through all the decks. I eventually emerged on top, where the swimming pool is. Finally I found the guy in charge of hospitality. He didn’t have any idea what was going on, either. At that point the ship wasn’t really tilting all that badly. It was easy to load people into the lifeboats. So I went down and started to help out there.”

For the next half-hour or so, lifeboats shuttled people into the harbor. When a few returned to the starboard side, scores of passengers marooned on the port side sprinted through darkened passageways to cross the ship and reach them. Amanda Warrick, an 18-year-old Boston-area student, lost her footing on the slanting, slippery deck and fell down a small stairwell, where she found herself in knee-deep water. “The water was actually rising,” she says. “That was pretty scary.” Somehow, carrying a laptop computer and a bulky camera, she managed to scramble 50 feet across the deck and jump into a waiting boat.

While there was plenty of chaos aboard the Concordia that night, what few have noted is that, despite confused crew members and balky lifeboats, despite hundreds of passengers on the edge of panic, this first stage of the evacuation proceeded in a more-or-less orderly fashion. Between 11, when the first lifeboats dropped to the water, and about 12:15—a window of an hour and 15 minutes—roughly two-thirds of the people on board the ship, somewhere between 2,500 and 3,300 in all, made it to safety. Unfortunately, it went downhill from there.

Rescue at Sea

Ahelicopter arrived from the mainland at 11:45. It carried a doctor, a paramedic, and two rescue swimmers from the Vigili del Fuoco, Italy’s fire-and-rescue service. A van whisked them from Giglio’s airfield to the port, where the swimmers, Stefano Turchi, 49, and 37-year-old Paolo Scipioni, pushed through the crowds, boarded a police launch, and changed into orange wet suits. Before them, the Concordia, now listing at a 45-degree angle, was lit by spotlights from a dozen small boats bobbing at its side. The launch headed for the port bow, where people had been jumping into the water. As it approached, a Filipino crewman on a high deck suddenly leapt from the ship, falling nearly 30 feet into the sea. “Stefano and I swam about 30 meters to rescue him,” Scipioni says. “He was in shock, very tired, and freezing cold. We took him ashore and then went back to the ship.”

It was the first of six trips the two divers would make in the next two hours. On the second trip they pulled in a 60-year-old Frenchwoman floating in her life jacket near the bow. “Are you O.K.?” Turchi asked in French.

“I’m fine,” she said. Then she said, “I’m not fine.”

Next they pulled in a second Frenchwoman in an advanced state of hypothermia. “She was shaking uncontrollably,” Scipioni recalls. “She was conscious, but her face was violet and her hands were violet and her fingers were white. Her circulatory system was shutting down. She kept saying, ‘My husband, Jean-Pierre! My husband!’ We took her ashore and went back.”

On their fourth trip they lifted an unconscious man into the police launch; this was probably the woman’s husband, Jean-Pierre Micheaud, the night’s first confirmed death. He had died of hypothermia.