- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Explore the glossary of poetic terms.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

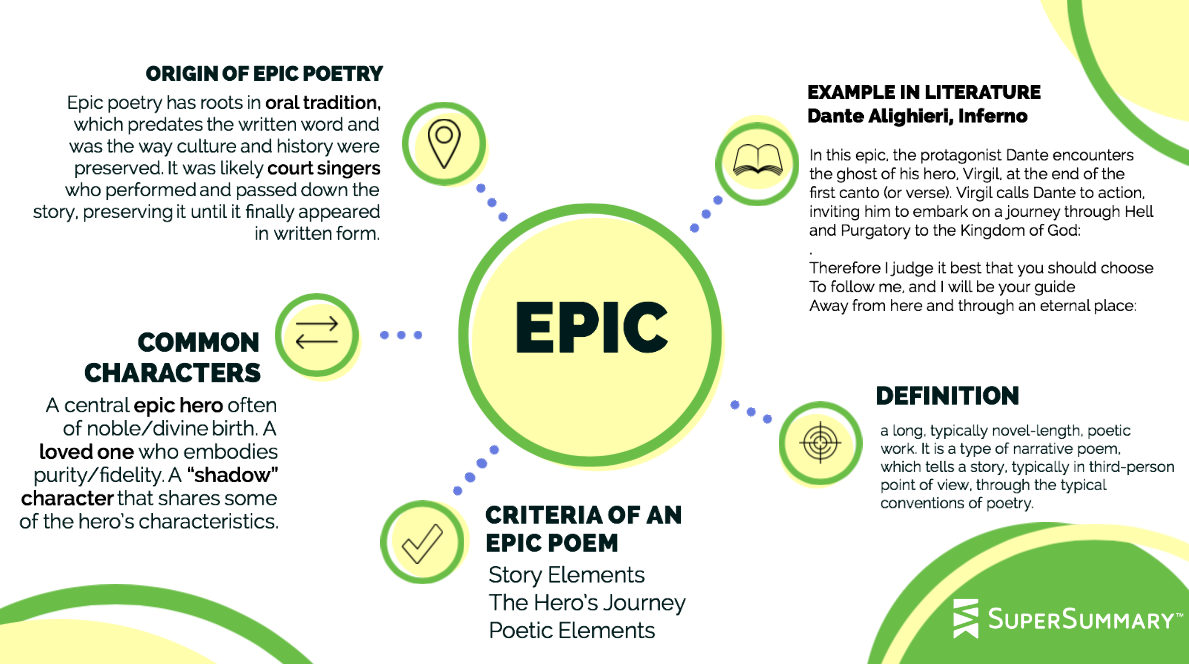

Epic is a long, often book-length, narrative in verse form that retells the heroic journey of a single person or group of persons.

Discover more poetic terms .

History of the Epic Form

The word “epic” comes from Latin epicus and from Greek epikos, meaning “a word; a story; poetry in heroic verse.” The elements that typically distinguish epics include superhuman deeds, fabulous adventures, highly stylized language, and a blending of lyrical and dramatic traditions, which also extend to defining heroic verse.

Many of the world’s oldest written narratives are in epic form, including the Babylonian Gilgamesh , the Sanskrit Mahâbhârata , the Thai Ramakien , Homer ’s Iliad and Odyssey , and Virgil ’s Aeneid . Both of Homer’s epics are composed in dactylic hexameter, which became the standard for Greek and Latin oral poetry. Homeric verse is characterized by the use of extended similes and formulaic phrases, such as epithets, to fill out the verse form. Greek and Latin epics frequently open with an invocation to the muse, as is shown in the opening lines of The Odyssey .

Over time, the epic has evolved to fit changing languages, traditions, and beliefs. Some epics of note include Beowulf , Edmund Spenser ’s The Faerie Queene , John Milton ’s Paradise Lost , and Elizabeth Barrett Browning ’s Aurora Leigh . The epic has also been used to formalize mythological traditions in many cultures, such as the Norse mythology in Edda and Germanic mythology in Nibelungenlied , and more recently, the Finnish mythology of Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala .

In the twentieth century and beyond, poets expanded the epic genre further with a renewed interest in the long poem with the canto . Examples such as The Cantos by Ezra Pound , Maximus by Charles Olson , The Anniad by Gwendolyn Brooks , The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You by Frank Stanford , The Iovis Trilogy by Anne Waldman , and Paterson by William Carlos Williams all push and pull at the boundaries of the genre, re-envisioning the epic through the lens of modernism .

Featured Poets

The following poets, as well as many others, are known for their work in the epic form.

Dante Alighieri : The author of La Commedia ( The Divine Comedy ), Dante Alighieri was born Durante Alighieri in Florence, Italy, in 1265.

Anne Carson : A poet, playwright, and classicist, Carson is the author of numerous genre-defying works that borrow from the epic form, including The Autobiography of Red .

Nazim Hikmet : Born in 1902 in what was then the Ottoman Empire, Hikmet went on to write multiple epic works, including Human Landscapes from My Country: An Epic Novel in Verse .

Homer : Credited with composing The Iliad and The Odyssey , Homer is arguably the greatest poet of the ancient world. Historians place his birth sometime around 750 BC.

John Milton : Born in London in 1608, Milton published multiple epic poems, including Paradise Lost and Samson Agonistes .

Virgil : Publis Vergilius Maro, most famously the author of the Aeneid , was born in northern Italy in 70 B.C.E.

Anne Waldman : Born in New Jersey in 1945, Anne Waldman is known for her work in mythopoetics and is the author of the feminist epic The Iovis Trilogy .

“By the time WWII broke out, H. D. was at the height of her idiosyncratic powers.... In Trilogy , her epic poem in three parts, written during World War II, she enters another phase of her writing—putting her visionary impulses to new uses. H. D. reports on war-torn London—not envisions, not invents or ennobles, but reports. The life of a bombed civilian city is of first importance; the speaker is one of its civilians.” —“ Shot Through with Brightness: The Poems of H. D. ”

“Milton cannot be said to have contrived the structure of an epic poem, and therefore owes reverence to that vigour and amplitude of mind to which all generations must be indebted for the art of poetical narration, for the texture of the fable, the variation of incidents, the interposition of dialogue, and all the stratagems that surprise and enchain attention. But, of all the borrowers from Homer, Milton is perhaps the least indebted.” —“ Blank Verse and Style: On John Milton ”

“Because epics, narrative poetry, and the voices that one grows up hearing were created by men, Notley says, female poets have suppressed what the female mind must have been like before the existence of the forms invented by men.... She writes, ‘there might be recovered some sense of what the mind was like before Homer, before the world went haywire & women were denied participation in the design & making of it....’ In this light, the quoted, collage-like aspect of her epic poem is particularly interesting, as if she's saying the female epic voice can only be quoted, but not generated whole.” —“ Finding the Female Voice: Alice Notley’s Poems and Collages ”

“Some of these long poems are epic (Waldman) and some anti-epic (Schuyler). Some are lyric sequences (Forché), some are hybrid texts (Waldman, Rankine, Williams), and some are book-length single poems with or without sections (Notley, Carson, Mayer, Sikelianos). Some are written in form (Koestenbaum) or look like prose (Stein) or read like a novel (Nelson). The form seems almost compelled to subvert (often by assimilating) genre categories. Still, long poems have more in common than just length, and the fact of their length alone is meaningful.” —Rachel Zucker, “ An Anatomy of the Long Poem ”

Related Poetic Terms

Oral-Formulaic Method : “Milman Parry (1902–1935) and his student Albert Lord (1912–1991) discovered and studied what they called the oral-formulaic method... referred to as ‘ oral-traditional theory, ’ ‘ the theory of Oral-Formulaic Composition, ’ and the ‘ Parry-Lord theory. ’ Parry used his study of Balkan singers to address what was then called the ‘ Homeric Question, ’ which circulated around the questions of ‘ Who was Homer? ’ and ‘ What are the Homeric poems? ’ ”—Edward Hirsch, A Poet's Glossary

Poetic Contest : “The poetic contest, a verbal duel, is common worldwide. It has been documented in a large number of different poetries as a highly stylized form of male aggression, a model of ritual combat, an agonistic channel, a steam valve, a kind of release through abuse. The poetic contest may be universal because it provides a socially acceptable form of rivalry and battle.” —Edward Hirsch, A Poet's Glossary

Verse Novel : “A novel in poetry. A hybrid form, the verse novel filters the devices of fiction through the medium of poetry. There are antecedents for the novelization of poetry in long narrative poems, in epics, chronicles, and romances, but the verse novel itself, as a distinct nineteenth-century genre, is different than the long poem that tells a story because it appropriates the discourse and language, the stylistic features of the novel as a protean form.” —Edward Hirsch, A Poet's Glossary

Read more poetic terms.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

8 Epic Journeys in Literature

Reading Lists

Micheline aharonian marcom, author of "the new american," recommends quest stories.

The journey story, where the hero must venture out into the world for reasons not necessarily entirely of his/her own devising, is likely as old as recorded literature.

Of course the journey story can also be understood as an allegory of the self, or soul, and its evolution in a lifetime, for storytelling is always an act, as Ann Carson says, “of symbolization.” In this sense, the journey story not only narrates the material events of a life, but also the interior transformations an individual undergoes.

As I wrote my seventh novel, The New American —which takes up the story of a young Guatemalan American college student at UC Berkeley, a DREAMer who is deported to Guatemala and his journey back home to California—I thought a lot about these kinds of archetypal stories in imaginative literature. Here are a few of my favorites.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, or He Who Saw Deep translated by Andrew George

The epic poem, one of oldest works of world literature, was composed in its earliest versions over 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia and written in Babylonian cuneiform on clay tablets. Much of the reason it is lesser known than the younger works of Homer is because the epic itself was not rediscovered until 1853, cuneiform was not deciphered until 1857, and it wasn’t well translated until 1912. Fragments of the story on stone tablets continue to be found in modern-day Turkey, Iraq and Syria.

The basic story follows the King Gilgamesh of Uruk (modern-day Warka, Iraq) and his friendship with the wild man Enkidu. They undergo various battles including fighting and defeating the bull of heaven. Later, upon Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh journeys to the edge of the earth where he goes in search of the secret of eternal life and, not finding it, returns home to Uruk having in some manner, in spite of life’s sorrows and travails, made peace with his own mortality.

“Ever do we build our households, ever do we make our nests, ever do brothers divide their inheritance, ever do feuds arise in the land. Ever the river has risen and brought us the flood, the mayfly floating on the water. On the face of the sun its countenance gazes, then all of sudden nothing is there!”

The Odyssey by Homer

Written down, along with the Iliad , soon after the invention of the Greek alphabet around the 8 th -century BCE, the epic poem sings of Odysseus’ return home after the Trojan War and his encounters with monsters, the Sirens, shipwrecks, and captivity by Calypso on her island until he finally makes it back to Ithaca. Because the poem survived more or less continuously until modern times and has had influence in so many cultures for millennia (unlike the more recently rediscovered and older Gilgamesh ), there’s no need to reiterate a narrative which so many of us already know, either directly or through the many stories the poem has inspired and influenced. One of my favorite moments comes in Book 14 when Odysseus finally makes it to Ithaca after ten years of traveling and, disguised as a beggar, seeks out Eumaeus the swineherd, who, not recognizing Odysseus, asks “But come…tell me of thine own sorrows, and declare me this truly, that I may know full well. Who art thou among men, and from whence?” These lines have seemed to me to in some way encapsulate some of storytelling’s most basic questions across the ages.

The Divine Comedy by Dante

Written after Dante had been sent into exile from his beloved city of Florence, the Commedia tells of the pilgrim’s descent into hell, his travel through purgatory, and eventually his ascent to paradise, with the Roman poet Virgil as his first guide, and later his beloved, Beatrice. The Commedia —the adjective “divine” in the title wasn’t added for several hundred years—begins with “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita/mi ritrovai per una selva oscura” which can be translated from the Italian to “Midway through the road of our life I found myself in a dark wood.” This is another line from literature that has haunted me for years, not only for the allegorical “dark wood” many of us might at times find ourselves lost in, but at Dante’s strange use of the word “our” even though the Commedia will tell of one pilgrim’s journey and search for the right way. The first person plural points, I think, to the common story of seeking meaning, understanding, and wisdom, and how in the case of this beautiful work, the company of literature with its manner of encoding in the song of language (even if you don’t speak Italian, read a few lines out loud and you can hear the poem’s rhythms) is a blessing in any reader’s life’s journey.

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, translated by John Rutherford

Alfonso Quixano has read too many chivalric romances (popular in 15 th and 16 th -century Europe), has gone mad from his reading, and now confuses reality with fantasy: he imagines himself the knight-errant Don Quixote and he determines to set off in search of adventure. From that premise, we journey through the countryside with our knight errant and his squire, Sancho Panza, as they slay giants (windmills) and defend the honor of his lady-love, Dulcinea del Toboso (a neighboring farm girl), who doesn’t actually ever appear in the story. In addition to being an amusing, laugh-out-loud tour de force of strange encounters as the pair travel across La Mancha, the reality of the violence, ignorance, and venality—not of Don Quixote, but of the society in which he lives in 17 th -century Spain—of corrupted clergy, greedy merchants, deluded scholars, and the like, is on full display. To this day, Don Quixote continues to reveal the joyous role of reading in our lives, how fictions make for all kinds of realities, and how very often it is the fool who sees the truth.

“When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams—this may be madness. Too much sanity may be madness—and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!”

Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih

Tayeb Salih’s mid 20th-century masterpiece is narrated by an unnamed young scholar who returns from England to his village on the Nile after seven years of study abroad and encounters a mysterious newcomer, Mustafa Sa’eed, who also lived for many years in the north. The novel takes up the many complexities and legacies of colonialism in post 1960s Sudan, the difficulties of encroaching modernity, the tragedy of Sa’eed’s life in England, and the intricate web of communal relationships in a traditional village. It is some of the women characters, especially the irreverent and bawdy storyteller, Bint Majzoub, very much like a storyteller out of the Nights , who regales the elder male listeners with bawdy tales, that has stayed in my imagination since I first read the book a decade ago. But it is the style of the book, its formal narrative complexity and interplay, the beauty of its prose, its deep and complex interrogation of the self in the world, that have made it a book I continue to return to. “How strange! How ironic! Just because a man has been created on the Equator some mad people regard him as a slave, others as a god. Where lies the mean?”

The Bear by William Faulkner

The journey here is into the woods to hunt Old Ben, the last remaining brown bear of his kind and stature in the quickly diminishing woods of Mississippi at the turn of the 19 th -century. As with so much of Faulkner’s work, the writing is sublime, the form strange, the land is a character, and we witness the maw of industrial capitalism as it reduces everything—animals, the land, people—to a ledger of profits and loss. The last scene of the illiterate woodsman, Boon, in a clearing—the land by then has been sold, Old Ben is dead, and loggers will imminently cut the remainder of the old woods down—sitting beneath a lone tree with squirrels running up and down its trunk screaming “They’re mine!” has long haunted me.

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

Italian writer Italo Calvino’s fantastical novel is about the imagined conversations between the 13th-century Venetian traveler, Marco Polo, and the Tartar Emperor Kublai Khan of the cities Polo has seen during his travels. The book, however, is mostly made up of descriptions of cities—fantastical forays not into any visible or historical cities, but imaginary invented ones: both ones that might have been and could be, and ones which perhaps did or do exist but are now transformed by the lens of story and distilled to their strange often wondrous essences. Calvino reminds us in this glorious book how the stories we tell greatly shape our thinking, our cultural formations, our views. “You take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders, but in the answer it gives to a question of yours.”

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

When I think of Hurston I recall her description in her essay “ How It Feels to Be Colored Me ” of the “cosmic Zora” who would emerge at times as she walked down Seventh Avenue, her hat set at a certain angle, who belonged “to no race nor time. I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads.” In Hurston’s extraordinary novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God , the eternal and timeless qualities of imaginative literature are on full display in the very specific groundings of place and time, spoken language and culture. The book opens with Janie Crawford recounting her life story to her friend Pheoby upon her return to the all-Black town of Eatonville, Florida. The book, set in the 1930s, follows Janie’s narration of her early life, her three marriages (the last for love), and the many trials she undergoes including the death of her beloved during her travels, before she finally returns changed, wiser, independent. “You got tuh go there tuh know there…Two things everybody’s got tuh do fuh theyselves. They got tuh go tuh God, and they got tuh find out about livin’ fuh theyselves.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Carmilla Is Better Than Dracula, And Here’s Why

Forget that dusty undead count—here's the sexy vampire we need right now

Oct 20 - Annabelle Williams Read

More like this.

9 Literary Mysteries With a Big Winter Mood

Stay inside with these cozy atmospheric books set in warm, dusty libraries and grand old houses

Jan 22 - Ceillie Clark-Keane

I Turned My Lover Into a McRib

"The McDonald's Boyfriend," flash fiction by Tom Kelly

Dec 13 - Tom Kelly

7 Books About Objects That Changed the World

Amy Brady, author of "Ice," recommends the secret histories behind everyday items

Nov 8 - Amy Brady

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

Definition of Epic

An epic is a long narrative poem that is elevated and dignified in theme , tone , and style . As a literary device, an epic celebrates heroic deeds and historically (or even cosmically) important events. An epic usually focuses on the adventures of a hero who has qualities that are superhuman or divine, and on whose very fate often depends on the destiny of a tribe, nation, or sometimes the whole of the human race. The Iliad , the Odyssey , and the Aeneid are considered the most important epics in western world literature, although this literary device has been utilized across regions and cultures.

Epic comes from the ancient Greek term epos , meaning story , word, poem. The Epic of Gilgamesh is considered by many scholars to be the oldest surviving example of a work of literature. This epic, traced back to ancient Mesopotamia in approximately 2100 BC, relays the story of Gilgamesh, an ancient king descended from the gods. Gilgamesh undergoes a journey to discover the secret of immortality.

Characteristics of an Epic

Though the epic is not a frequently used literary device today, its lasting influence on poetry is unmistakable. Traditionally, epic poetry shares certain characteristics that identify it as both a literary device and poetic form. Here are some typical characteristics of an epic:

- written in formal, elevated, dignified style

- third-person narration with an omniscient narrator

- begins with an invocation to a muse who provides inspiration and guides the poet

- includes a journey that crosses a variety of large settings and terrains

- takes place across long time spans and/or in an era beyond the range of living memory

- features a central hero who is incredibly brave and resolute

- includes obstacles and/or circumstances that are supernatural or otherworldly so as to create almost impossible odds against the hero

- reflects concern as to the future of a civilization or culture

Famous Examples of Literary Epics

Epic poems can be traced back to some of the earliest civilizations in human history, in Europe and Asia, and are therefore some of the earliest works of literature as well. Literary epics reflect heroic deeds and events that reveal significance to the culture of the poet. In addition, epic poetry allowed ancient writers to relay stories of great adventures and heroic actions. The effect of epics was to commemorate the struggles and adventures of the hero to elevate their status and inspire the audience .

Here are some famous examples of literary epics:

- The Iliad and The Odyssey : epic poems attributed to Homer between 850 and 650 BC. These poems describe the events of the Trojan War and King Odysseus’s return journey from Troy and were initially conveyed in the oral tradition.

- The Mahābhārata: an epic poem from ancient India composed in Sanskrit.

- The Aeneid : epic poem composed in Latin by Virgil, a Roman poet, between 29 and 19 BC. This is a narrative poem that relates the story of Aeneas, a Trojan descendent and forebear to the Romans.

- Beowulf : an epic poem was written in Old English between 975 and 1025 AD. It is not attributed to an author, but is known for the conflict between Beowulf , a Scandinavian hero, and the monster Grendel.

- The Nibelungenlied: the epic narrative poem was written in Middle High German, c. 1200 AD. Its subject is Siegfried, a legendary hero in German mythology.

- The Divine Comedy : epic poem by Dante Alighieri and was completed in 1320. Its subject is a detailed account of Dante as a character traveling through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven.

- The Faerie Queene : an epic poem by Edmund Spenser published in 1590 and given to Elizabeth I. This poem features an invocation of the muse and is the work in which Spenser invented the verse form later known as the Spenserian stanza .

- Paradise Lost : written by John Milton in blank verse form and published in 1667. Its subject is the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden as well as the fallen angel Satan.

Difference Between Epic and Ballad

Both epic and ballad works date back to ancient history and were passed down from one generation to another through oral poetry. However, these literary devices feature significant differences. An epic is an extended narrative poem composed with elevated and dignified language that celebrates the acts of a legendary or traditional hero. A ballad is also a narrative poem that is adapted for people to sing or recite and intended to convey sentimental or romantic themes in short stanzas, usually quatrains with repeating rhyme scheme . Ballads typically feature common, colloquial language to represent day-to-day life, and they are designed to have universal appeal to humanity as a group. Epic works, however, focus on a certain culture, race, nation, or religious group whose victory or failure determines the fate of an entirety of a nation or larger group but not all of humanity.

Characters in Epic Poetry

An epic poem can have several characters but the main character is always a historical figure or a legendary hero. Such heroes are of noble birth, having superhuman capabilities, with supernatural elements to help them out in difficult situations. He could be an unparalleled warrior, demonstrating superhuman capabilities before superhuman foes. Other characters could be all and sundry, animals , gods and goddesses, and some other superhumans but not equal to the legendary hero. Its classical examples are Odyssey and Illiad . Paradise Lost is the best example of an epic in English Literature.

Features of Main Character in Epic Poetry

The main traits of the central character of an epic are as follows.

- The hero is of a noble birth such as Odysseus.

- He could have superhuman capabilities.

- He is a good traveler and travels to foreign lands.

- He is a matchless warrior and could fight supernatural beings.

- He is a cultural legend and people sing in his praise.

- He is a humble, sympathetic and compassionate fellow.

- He surmounts all obstacles including supernatural foes.

Structure of Epic Poetry

There are several important points in the structure of an epic poem.

- The first line states the theme of the poem such as in Paradise Lost .

- The poem invokes a Muse that has inspired and instructed the poet to write the poem.

- The poem opens from the middle or In Medias Res and then states the main events.

- The poem includes lists or catalogs of characters, armies, or ships.

- The poem includes long speeches of the main warriors.

- The poem has extended metaphors and extended similes written in iambic pentameter .

Use of Supernatural Characters in Epic Poems

Epic poems often comprise supernatural characters. Some have gods and goddesses such as in Gilgamesh and Odyssey . They help heroes in difficult times. Some have demons and monsters with whom heroes battle and win. Some epics have other supernatural elements with whom the heroes come into contact and win such as Cyclops in Odyssey. Some have mythical creatures such as Eris, Thetis, Enkidu, and Shamas in Gilgamesh.

Origin of Epic Poetry

Gilgamesh is perhaps the earliest known epic that has survived the ravages of time. It is a Sumerian poem of King Gilgamesh and has been traced back to 3,000 BC. It is stated to have the records of King Gilgamesh. Following that, Mahabharta , the ancient Indian epic, was written in 300BC and comprises more than 200,000 verses, the longest epic. Odyssey, Illiad, Paradise Lost, Ramayana, and Shahnameh are some other popular epics of different regions.

Examples of Epics in Literature

Modern readers may consider any lengthy tale of an ancient hero who embarks on a significant journey to be an epic work. However, though this type of heroic story is common in various forms of literature, prose narratives aren’t considered part of the realm of the epic tradition. It’s rare for modern poets to choose epic as a literary device; however, epic poetry remains one of the most influential forms of literature.

Here are some examples of epic poems in literature:

Example 1: Inferno (first canticle of The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri)

i am the way into the city of woe, I am the way into eternal pain, I am the way to go among the lost. Justice caused my high architect to move, Divine omnipotence created me, The highest wisdom, and the primal love. Before me there were no created things But those that last forever—as do I. Abandon all hope you who enter here.

This passage is from the first canticle of Dante’s Divine Comedy , Inferno , in which the character Dante makes a journey through Hell guided by the ancient Roman poet, Virgil. As Dante approaches the Gate of Hell, he finds these lines inscribed. The poetic lines represent the “ voice ” of Hell in telling Dante and the reader of Hell’s nature, origin, and purpose. This indicates the pathway of what is to come for Dante on his journey through the epic poem. The inscription describes Hell as a city, structured as a contained geographical area bound by walls and harboring a population of souls suffering various levels and means of torment. This is a parallel for the canticle Paradiso and its portrayal of Heaven, which is described by Virgil as the city of God.

In addition, the inscription warns that Hell is a place of eternal woes, pain, and loss. Dante witnesses God’s intense punishment of those who sin, lending to Dante’s journey an otherworldly setting that crosses a span of time and memory. The last line of the inscription is an example of the elevated language and tone of Dante’s epic poem. Dante’s character, as well as the reader, are told to “abandon all hope” upon entering the gate of Hell, implying there is no escape from the Inferno with hope intact. Dante’s epic poem is one of the most influential works in the history of literature.

Example 2: Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto

This dog won’t hunt. This horse won’t jump. You get the general drift. However, he keeps on trying, but the fire won’t burn, the kindling is wet, and the faint glow of the ember is weak and dying. He has no other choice then but to let It go and take a nap on the ground there, lying Next to her—for whom Dame Fortune has more Woes and tribulations yet in store.

Ariosto’s epic poem of 1532 is an interpretation of the battles between the Saracen invaders and the Franks. Orlando Furioso is a brave warrior tasked to save his people, indicating a heroic character who is courageous and resolute. However, he suffers from a period of madness due to the seductions of Angelica. This circumstance represents an obstacle for the hero to overcome as a means of fulfilling his journey and destiny in ensuring the salvation of his people. The pairing of valiant duty and passionate love is common in epic poetry. In Ariosto’s work, Furioso ultimately recognizes passion as a weakness not befitting of a knight and he, therefore, returns to placing the importance of duty before any other action.

Example 3: Don Juan by Lord Byron

Between two worlds life hovers like a star, ‘Twixt night and morn, upon the horizon’s verge. How little do we know that which we are! How less what we may be! The eternal surge Of time and tide rolls on, and bears afar Our bubbles; as the old burst, new emerge, Lash’d from the foam of ages; while the graves Of Empires heave but like some passing waves.

Some poets, including Alexander Pope, wrote mock-epics to satirize heroic verse and its elevated stature which became epic works of their own. In “Don Juan,” Byron utilizes the elements of epic as a literary device to reinvent the story of the title character from the Spanish legend of “Don Juan.” However, in Byron’s work, the story of Don Juan is reversed. Rather than portraying the infamous character as a womanizer, he is presented as someone who is easily seduced by women. This allows Byron as a poet to satirize the legend and character of Don Juan in addition to the epic form of poetry as well.

However, though Byron’s epic poem is satirical, it is also masterful in its sixteen cantos of ottava rima or eighth rhyme . “Don Juan” features 16,000 lines in which Byron cleverly utilizes elevated language and tone as a nod to traditional epic poetry, but also intersperses a vulgar style of writing as well to subvert the epic tradition.

Synonyms of Epic

The distant synonyms for epic are a heroic poem, saga, legend, lay, romance , myth , history, chronicle, folk tale, long story, and long poem.

Related posts:

- 15 Epic Uses of Apostrophe in The Iliad

Post navigation

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

epic noun & adjective

- Hide all quotations

Earlier version

- epic, a. and n. in OED Second Edition (1989)

What does the word epic mean?

There are nine meanings listed in OED's entry for the word epic , one of which is labelled obsolete. See ‘Meaning & use’ for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence.

epic has developed meanings and uses in subjects including

How common is the word epic ?

How is the word epic pronounced, british english, u.s. english, where does the word epic come from.

Earliest known use

The earliest known use of the word epic is in the late 1500s.

OED's earliest evidence for epic is from 1583, in the writing of Brian Melbancke, writer.

epic is a borrowing from Latin.

Etymons: Latin epicus .

Nearby entries

- epibenthic, adj. 1902–

- epibenthos, n. 1902–

- epibiont, n. 1949–

- epibiotic, adj. & n. 1930–

- epiblast, n. 1866–

- epiblema, n. 1861–

- epibolic, adj. 1875–

- epiboly, n. 1875–

- epiboulangerite, n. 1872–

- epibranchial, adj. 1846–

- epic, n. & adj. 1583–

- epical, adj. & n. 1668–

- epically, adv. 1804–

- epicalyx, n. 1847–

- epicanthal, adj. 1893–

- epicanthic, adj. 1877–

- epicanthus, n. 1833–

- epicardiac, adj. 1848–

- epicardial, adj. 1869–

- epicardium, n. 1860–

- epicaridan, n. & adj. 1855–

Meaning & use

Were it meete that Ennius excelling in Epicks , shoulde dispraise Cecilius a Comicall Poet.

Epiques chang'd to Doleful Elegies.

One of them was the Goddess of Elegies..and another of Epicks .

He [ sc. Mr. M'Pherson] brought forward his counterfeit epicks [ sc. the alleged poems of Ossian] .

Rose-coloured novels and iron-mailed epics .

The most popular of all English poems has been the Puritan epic of the ‘Paradise Lost’.

It is perhaps only an accident that the Greek epics are put in verse at all.

The ox units mentioned in the Homeric epics .

The dominant female in Virgil's epic is the frightening Juno.

- epic 1583– A poem, typically derived from ancient oral tradition, which celebrates in the form of a continuous narrative the achievements of one or more…

- epopee 1697– An epic poem (= epic , n. ). Usually the epic poem generically; the epic species of poetry.

- epopoeia 1749– = epopee , n. 1.

- epos 1855– An epic poem: = epic , n. , epopee , n.

Fenelon's Telemachus, is an Epic in prose.

That great prose poem, the single epic of modern days, Thomas Carlyle's ‘French Revolution’.

I want very much to see the Birth of a Nation , which is said to be a really great film, an epic in pictures.

Nash's ..ran the last Forsyte epic as a serial.

An ‘ epic ’ is a large-scale film in which the events, usually historical, take precedence over the ‘love interest’.

Epics don't require sand or falling temples.

- romantic comedy 1748– (Originally) a comedy having qualities associated with a literary romance (cf. romantic , adj. A.1a); (subsequently also) a film or other work…

- epic 1785– A book, film, or other creative work resembling or likened to a traditional epic, esp. in portraying heroic deeds and adventures or covering an…

- pre-release 1871– A release in advance; esp. a film, record, etc., given restricted availability before being generally released.

- foreign film 1899– A film produced in a foreign country, now esp. one that requires the addition of subtitles or dubbing; a foreign-language film (also used as a…

- frivol 1903– Something frivolous, (an instance of) frivolity; a frivolous or light-hearted event, etc. (esp. a literary or cinematographic production); also, a…

- dramedy 1905– A work of art exhibiting qualities of both drama and comedy. In later use: spec. a television programme or film in which the comedic elements are…

- film loop 1906– a. A slack length of film, forming a loop, necessary for the smooth running of a film strip in a projector; = loop , n.¹ 4i; b. a (short) film spliced…

- first run 1910– a. adj. Designating a film being shown for the first time or a cinema in which films are normally first shown; b. n. the first showing or première…

- detective film 1911–

- colour film 1912– A cinema film (or formerly a photograph) produced in natural colours.

- news film 1912–

- topical 1912– A film dealing with topical events. (Now disused .)

- cinemicrograph 1913– A moving image of a microscopic object, process, etc., typically obtained by means of time-lapse photography. Cf. cinemicrography , n.

- scenario production 1913– a. The production of film scripts or scenarios; b. = scenario picture , n. (now rare ).

- scenic 1913– A film whose subject is natural scenery, or a series of photographs of natural scenery shown as a film; (more generally) a text, painting…

- sport 1913– A cinematographic film about sport. rare .

- newsreel 1914– A short cinema film dealing with news and current affairs. Also in extended use.

- serial 1914– A film drama shown in cinemas in sequential instalments. Cf. cliffhanger , n. Now historical .

- scenario picture 1915– A film for which a plot and storyline are created, as opposed to a documentary or factual film; also figurative .

- sex comedy 1915– A play, film, or television programme which combines erotic and comic elements, or whose plot centres on romantic relationships or sexual encounters.

- war picture 1915– a. A painting of which the theme is war; b. a photograph of a scene from the theatre of war; also, a documentary film of action from a war, and trans …

- telefilm 1919– A film or motion picture, esp. one shown on television or one made for that medium rather than for release at the cinema.

- comic 1920– A comic film, animation, or programme for cinema or television, esp. a cinematic short shown before the feature film.

- true crime 1923– A genre of writing, film, etc., in which real crimes are examined or portrayed; cf. true , adj. A.II.4c; frequently (and in earliest use) attributive.

- art house 1925– A cinema which specializes in films of artistic rather than commercial appeal, esp. foreign, experimental, or independent films. Hence: this style…

- psychological thriller 1925– A novel, film, etc., in the thriller genre which focuses on the psychology of its characters, or which psychologically manipulates its audience or…

- quickie 1926– A film or television programme that is made quickly and cheaply. Cf. quota quickie , n.

- turkey 1927– U.S. slang . An inferior or unsuccessful cinematographic or theatrical production, a flop; hence, anything disappointing or of little value.

- two-reeler 1928–

- smellie 1929– A (hypothetical) cinema or television film in which smell is synchronized with the picture. Usually plural. Cf. feelie , n.

- disaster film 1930– a. A factual film concerning a disaster (now rare ); b. a film whose plot centres on a disaster, esp. one involving many people; such films as a…

- musical 1930– Originally U.S. A play or film in which singing and dancing play an essential part; a musical comedy.

- feelie 1931– A (hypothetical) motion picture augmented by tactile effects which are felt by the viewer. Chiefly in plural (frequently with the ): the screening of…

- sticky 1934– A slow-moving film.

- action comedy 1936– A film or television programme which blends comedy with a lively plot and fast-paced action; cf. action film , n. , situation comedy , n.

- quota quickie 1936– = quota film , n.

- re-release 1936– A recording or film that is re-released, esp. a recording that is released on a different format from before.

- screwball comedy 1937– a. A comedy film of a type first produced in the United States in the 1930s, with a fast-moving, irreverent style, typically featuring eccentric…

- story film 1937– A film that tells a story, esp. a fictional feature film.

- telemovie 1937– A film shown on television, esp. one made for that medium rather than for release at the cinema; cf. telefilm , n. 1.

- disaster movie 1939– A film whose plot centres on a disaster, esp. one involving many people; such films as a genre.

- pickup 1939– Film (originally U.S. ). A film, or film footage, which is made by one company and acquired (for distribution, etc.) by another.

- video film 1939– a. U.S. cinematographic film used to pre-record television programmes ( rare ); b. U.S. (now disused ) a cinematographic film of a television broadcast…

- actioner 1940– colloquial . An action film.

- space opera 1941– A science fiction story or drama set in space; space fiction esp. of an unsophisticated or clichéd type.

- telepic 1944– A film shown on television, esp. one made for that medium rather than for release at the cinema; cf. telefilm , n. 1.

- biopic 1947– A biographical film, esp. one dramatizing the life of a public or historical figure.

- kinescope 1949– A film recording made from a television broadcast.

- TV movie 1949– a. A film recording of a television broadcast (now disused ); b. a movie shown on television, esp. one specially made for that medium rather than…

- film noir 1950– A film characterized by a mood of cynicism, fatalism, menace, and moral ambiguity, typically taking place in an urban setting.

- pièce noire 1951– A play or film with a sombre or macabre theme. Cf. film noir , n. & adj.

- pièce rose 1951– A light or entertaining play or film; a comedy.

- deepie 1953– A film made so as to give a viewer the illusion of three-dimensional depth; a 3-D film.

- misterioso 1953– An air of mystery; mysteriousness. Also: a film, television programme, etc., whose story relies on mystery and suspense.

- film noir 1956– A genre of crime film or thriller film characterized by a mood of cynicism, fatalism, menace, and moral ambiguity, and having a (typically…

- mockumentary 1956– A film, television programme, etc., which adopts the form of a serious documentary in order to satirize its subject.

- policier 1956– A film based on a police novel. Also occasionally: a police novel. Cf. roman policier , n.

- psychodrama 1956– A play, film, novel, etc., in which psychological elements are the main interest.

- free film 1958– A film made in accordance with the aims of the Free Cinema movement.

- prequel 1958– A book, film, etc., narrating events which precede those of an already existing work.

- co-production 1959– A joint production; the process or result of financing the production of (or, more rarely, of producing) something, esp. a film or television…

- glossy 1960– Cinematography . A film depicting fashionable life.

- sexploiter 1960– A sexually exploitative film.

- monster movie 1961– A film having a monster as a major feature of the action.

- sci-fier 1961– = science-fictioner , n.

- tie-in 1962– A book, film, or the like published to take advantage of the appearance of the same work in another medium.

- chanchada 1963– A type of popular Brazilian musical film, typically characterized by slapstick or burlesque humour, vibrant song and dance sequences, and the…

- romcom 1963– A film with a light, comedic tone and a plot centring on a romance (often viewed in a sentimental or idealized way); a romantic comedy; (also) the…

- wuxia 1963– An itinerant swordsman or warrior of ancient China. Frequently attributive , esp. designating a genre of Chinese historical fiction or martial…

- chick flick 1964– A film predominantly based around female characters; spec. (a) a film designed to appeal to male sexual fantasy in its exploitative portrayal of…

- showreel 1964– A short film, video, etc., containing examples of an actor's, director's, or company's work for showing to potential employers or customers; a…

- monster film 1965– = monster movie , n.

- sword-and-sandal 1965– A genre of film characterized by a setting in the ancient world, often featuring characters from the Bible or classical history and myth…

- schlockbuster 1966– A film or book which is highly popular or commercially successful but is regarded as having no artistic merit. Cf. schlocker , n.

- mondo 1967– A film which is reminiscent or imitative of Mondo Cane (see etymological note), esp. one with voyeuristic or pornographic elements. rare .

- peplum 1968– A film within a genre that flourished in Italy in the late 1950s and early 1960s, typically featuring an ancient world setting, an adventurous and… Though frequently popular worldwide, the relatively low production values and poor dubbing of many of these films meant that peplum was often used somewhat depreciatively.

- thriller 1968– One who or that which thrills; spec. ( slang or colloquial ) a sensational play, film, or story (cf. shocker , n.² A.1b).

- whydunit 1968– A story, play, or film in which the main interest lies in the detection of the motive for some crime or other action.

- schlocker 1969– A film regarded as having no artistic merit; esp. a schlock horror film. Cf. schlockbuster , n.

- road movie 1970– A film in which the principal character or characters make a journey by road, typically a journey on which some form of insight or self-knowledge…

- blaxploitation 1972– As a modifier, designating a type of film exploiting a popular trend or taste for stereotypical urban African American characters, settings, and…

- buddy-buddy movie 1972– A movie portraying a close friendship between two people of the same sex, typically men; cf. buddy movie , n.

- buddy-buddy film 1974– A film portraying a close friendship between two people of the same sex, typically men; cf. buddy film , n.

- buddy film 1974– A film portraying a close friendship between two people of the same sex, typically men; a buddy movie; cf. buddy-buddy film , n.

- science-fictioner 1974– A science fiction film or television programme.

- screwball 1974– Originally U.S. Film . A genre of comedy film first produced in the United States in the 1930s, with a fast-moving, irreverent style, typically…

- buddy movie 1975– A movie portraying a close friendship between two people of the same sex, typically men; cf. buddy-buddy movie , n.

- slasher movie 1975– attributive . Designating cinematographic films which depict the activities of a vicious attacker whose victims are slashed with a blade, as slasher …

- swashbuckler 1975– A book, film, or other work portraying swashbuckling characters.

- filmi 1976– a. The films produced by the Mumbai film industry ( rare ). b. A type of music used in the soundtracks of these films (see sense A); = filmi geet , n.

- triptych 1976– transferred . Cinematography . A sequence of film designed to be shown on a triple screen, using linked projectors.

- autobiopic 1977– A film based on events in the life of the filmmaker; an autobiographical film. Cf. biopic , n.

- Britcom 1977– A comedy film produced or set in the United Kingdom; a British comedy film.

- kidflick 1977– A cinematographic or video film for children; = kidvid , n.

- noir 1977– A genre of crime film or detective fiction characterized by cynicism, sleaziness, fatalism, and moral ambiguity; film noir. Also: a film or novel in…

- bodice-ripper 1979– A sexually explicit romantic novel, esp. one in a historical setting with a plot involving the seduction of the heroine; also transferred , a film…

- monster flick 1980– = monster movie , n.

- chopsocky 1981– A violent action film featuring (numerous) sequences involving martial arts, esp. kung fu. Also: the martial arts themselves, as depicted in such…

- date movie 1983– A film that might be suitable for watching on a date ( date , n.² 8a), esp. one which is pleasant but somewhat innocuous, such as a romantic comedy.

- kaiju eiga 1984– A genre of Japanese film having a giant monster as a major feature of the action; a film of this genre (or one in a similar style made…

- screener 1986– An advance copy or promotional video, DVD, etc., of a film, television programme, etc.

- neo-noir 1987– This style or genre; (also) a film or novel in this style.

- tent pole 1987– figurative and in figurative contexts. Film . A big-budget film which is expected to generate sufficient revenue or attention to support a range of…

- indie 1990– An independent film (or, later, television) producer or production company; an independently produced film or programme; by extension applied to…

- bromance 2001– Intimate and affectionate friendship between men; a relationship between two men which is characterized by this. Also: a film focusing on such a…

- hack-and-slash 2002– Relating to or designating a film, interactive game, etc., which focuses chiefly on combat and violence. Cf. slasher , n. additions. Also…

- tokusatsu 2004– A genre of Japanese film or television entertainment characterized by the use of practical special effects, usually featuring giant monsters…

- zom-com 2004– A comedy film featuring zombie characters.

- mumblecore 2005– A style of low-budget film typically characterized by naturalistic and (apparently) improvised performances, a reliance on dialogue rather than…

- independent 2006– A person or company producing films without the affiliation or backing of a major established studio; an independent filmmaker (cf. indie , n. A.1)…

- dark fantasy 2007– A work of fiction, as a novel, film, etc., combining elements of horror and fantasy, typically sinister, bleak, or disturbing in tone or subject…

- hack-and-slay 2007– = hack-and-slash , adj. Also as n.

- gorefest 2012– A scene or description of bloodshed and gory violence; (now esp. ) a film characterized by scenes of graphic violence and bloodshed.

- kidult slang (originally and chiefly U.S. ). Frequently derogatory . A television programme, film, or other entertainment intended to appeal to both children and adults.

It cannot be denied but that Virgil excelled all the Epickes [French ceux qui auparauant auoyent escrit des vers heroicques ] .

Now to like of this, Lay that aside, the Epicks office is [Latin promissi carminis auctor ] .

The Epics are not more exact in describing Times and Seasons, than our Poet.

- heroic 1594–1680 A writer of heroic verse, a heroic poet. Obsolete .

- epic 1607–1744 A poet who composes epics. Obsolete .

- epo-poet 1800– An epic poet.

- epicist 1820– An epic poet; a creator of epics.

- epopoeist 1840– One who writes epic poetry.

- epoist 1842– A writer of epic poetry.

The best Masters of the Epick , Homer, and Virgil.

Aristotle distinguishes Poesie into three divers kinds of perfect Poems, the Epick , the Tragick, and the Comick [French l'Epopée, la Tragedie, & la Comedie ] .

From this Fountain sprung up Satyrical Poetry, even as from the Effects of Love and Courage, came the Epic and the Tragic.

How Tragedy and Comedy embrace; How Farce and Epic get a jumbled race.

The Play in Hamlet, in which the Epic is substituted for the Tragic in order to make the latter be felt as the real-Life Diction.

Our literature is rich in ballads, a form epitomical of the epic and dramatic.

Homer and the epic .

Most frequent in bucolic, elegiac, and dramatic poetry, the adynaton finds a place also in epic , lyric, and satire.

Aristotle..discussed tragedy, comedy and epic as separate genres.

Tragic poetry can be as independent from performance as the epic is.

This starry and dreamlike incident in the epic of life's common career.

That life was a noble Christian epic .

Before middle age he has lived an epic .

The financing of this little pike was an epic in itself.

The Government yesterday launched a mighty enterprise—nothing less than the occupational enfranchisement of the country's youth. Yet this [is] an epic without glamour.

Laurie Spina knew the moment he saw the crowd of 11,000..that the 1982 Foley Shield grand final would be an epic .

- epic 1833– An event or series of events likened to those in an epic, esp. in being grand in scale or lengthy and arduous.

- epos 1848– transferred . A series of striking events worthy of epic treatment.

Harding a Poet Epick or Historicall.

Teaches what the laws are of a true Epic poem.

The same images serve equally for the Epique Poesie, and for the Historique and Panegyrique.

Three and twenty Descriptions of the Sun-rising that might be of great Use to an Epick Poet.

To be poor, in the epick language, is only not to command the wealth of nations.

My poem's epic , and is meant to be Divided in twelve books.

The epic poet..must drink water out of a wooden bowl.

Tennyson has endeavored to imitate the old epic simplicity.

Some of the Scandinavian ballads dealing with the old historical traditions are merely re-readings of older epic poems.

Homer reveals the world of gods as well as the world of men, both in epic verse.

It is clear that the epic genre, starting from Virgil, and especially after Lucan, builds its identity on an intersection between the epic and the tragic canons.

A common early epic line that describes a warrior putting a helmet on his head in preparation for battle.

- heroical ?1521– = heroic , adj. A.2b.

- heroic a1586– Of a poet, poetry, etc.: having mythological or historical heroes as subject matter (cf. sense A.3); epic. Cf. mock-heroic , adj.

- epic 1589– Of or relating to the genre of poetic composition, typically derived from ancient oral tradition, which celebrates in the form of a continuous…

- epical 1694– Of a poem or other work: belonging to the epic genre; of the nature of an epic. Also: designating an epic poet. Cf. epic , adj. B.1.

This day was published.. The Bonze ; or, Chinese Anchorite. An oriental epic novel.

Mr. Walter Savage Landor..author of an epic piece of gossiping called Gebir.

The last landscape..is entitled the ‘The Mountain Top’... This composition is..the most epic work that this artist ever produced.

Of these Irish epic tales, ‘The Destruction of Dà Derga's Hostel’ is a specimen of remarkable beauty and power.

Mr Steinbeck's novel..is a deliberately and self-consciously epic account of the agrarian revolution in America.

Kevin Costner makes his directorial debut in ‘Dances with Wolves’, a three-hour epic film in which he also stars.

- watery c1230– Of speech, style, emotion, a person, etc.: vapid, insipid; lacking in substance or interest; thin, feeble, weak.

- polite ?a1500– Of language, the arts, or other intellectual pursuits: refined, elegant, scholarly; exhibiting good or restrained taste.

- meagre 1539– Deficient, inferior. Of writing, artistic work, etc., or its style or subject matter: lacking fullness or elaboration; weak, unsatisfying.

- over-laboured 1579– Overworked; (also) excessively elaborate or laboured. Also as n.

- bald 1589– Bare or destitute of ornament and grace; unadorned, meagrely simple. Of literary style.

- spiritless 1592– Lacking dynamic qualities; characterized by the absence of animation, energy, or zest. Of a thing, esp. a literary or artistic work.

- light 1597– Of literature, music, or other creative works: designed to be entertaining rather than thought-provoking.

- meretricious 1633– Alluring by false show; showily or superficially attractive but having in reality no value or integrity.

- standing 1661–1709 Of a work of art or literature: regarded as enduring or exemplary. Cf. standard , adj. B.I.3a. Obsolete .

- effectual 1662 Powerful in effect, having powerful effects; = effective , adj. A.1. Now rare .

- airy 1664– Like air in its lightness and buoyancy. Light, delicate, graceful in style or execution. Also, of a person or work of art: ingenious, witty.

- severe 1665– In reference to style or taste, literary or artistic: Shunning redundance or unessential ornament; not florid or exuberant; sober, restrained…

- correct 1676– In accordance with an acknowledged or conventional standard, esp. of literary or artistic style, or of manners or behaviour; proper.

- enervate a1704– Of artistic style, etc.

- free 1728– Of a literary, musical, or other artistic composition: not observing the normal conventions of style or form; (of a translation) conveying only the…

- classic 1743– = classical , adj. A.7.

- academic 1752– Conforming to the principles of an academy of arts, esp. painting, often too rigidly; conventional, esp. in an excessively formal way.

- academical 1752– = academic , adj. B.4. Now rare .

- chaste 1753– Pure in artistic or literary style; without meretricious ornament; chastened, subdued.

- nerveless 1763– Of literary or artistic style: diffuse, insipid, lifeless.

- epic 1769– Designating a book, film, or other creative work resembling or likened to an epic poem; dealing with heroic exploits and adventures, esp. in a…

- crude 1786– Of literary or artistic work: Lacking finish, or maturity of treatment; rough, unpolished.

- effective 1790– Of a work of art, a design, a literary composition, etc.: producing a striking or pleasing impression.

- creative 1791 Inventive, imaginative; of, relating to, displaying, using, or involving imagination or original ideas as well as routine skill or intellect, esp…

- soulless 1794– spec. Of literature, art, music, etc.: devoid of inspiration or feeling; cold, mechanical.

- mannered 1796– Of art, architecture, etc.: characterized by or given to mannerism; artificial, affected, or over-elaborate in style.

- manneristical 1830– = manneristic , adj.

- manneristic 1837– Mannered, characterized by mannerisms of behaviour, style, etc.; spec. characterized by Mannerism in art, architecture, etc.

- subjective 1840– Art and Literary Criticism . Expressing, bringing into prominence, or deriving its materials mainly from, the individuality of the artist or author.

- inartistical a1849– Not artistical; = inartistic , adj.

- abstract 1857– Designating music, dance, film, etc., which rejects representation of or reference to external reality, esp. in dispensing with narrative…

- inartistic 1859– Not artistic; not in accordance with the principles of art.

- literary 1900– Of the visual arts, music, etc.: concerned with depicting or representing a story or other literary work; that refers or relates to a text; that… Sometimes in a derogatory sense, implying dependency on a text at the expense of freedom of expression.

- period 1905– Belonging to or characteristic of a particular historical period; deliberately old-fashioned or archaic in style, subject matter, etc.

- atmospheric 1908– Evoking or designed to evoke an atmosphere (sense 4).

- dateless 1908– Perpetually relevant, valuable, appealing, etc.; not dated; classic, timeless.

- atmosphered 1920– Having or provided with atmosphere (sense 4).

- non-naturalistic 1925– = non-naturalist , adj. A.3.

- self-indulgent 1926– Chiefly depreciative . Of a literary, artistic, or other creative work: catering to or concerned with the creator's own tastes or preoccupations, without regard to…

- free-styled 1933– Not observing conventions of style or form; improvisational, unrestrained. Cf. freestyle , adj. A.2.

- soft-centred 1935– Essentially weak, vulnerable, or sentimental in nature. Usually somewhat depreciative .

- freestyle 1938– Of a literary, musical, or artistic work or performance: = free , adj. A.II.10b.

- pseudish 1938– Often with capital initial. Osbert Lancaster's mock or depreciative name for: a style or supposed ‘school’ of architecture regarded as imitative or…

- decadent 1942– Said of other schools of literature and art characterized by decadence; spec. = aesthetic , adj. B.3.

- post-human 1944– Designating or relating to art, music, etc., in which humanity or human concerns are regarded as peripheral or absent; abstract, impersonal…

- kitschy 1946– Esp. of art, objects, design, and entertainment: having popular appeal but considered to be vulgar, of low quality, or lacking artistic merit, esp…

- faux-naïf 1958– Of a work of art: self-consciously or meretriciously simple and artless.

- ultra-processed 1961– Of a film, piece of music, or other artistic work: produced in such an elaborate way that the energy, spontaneity, or artistry of the original…

- spare 1965– Of style: unadorned, bare, simple.

- binge-worthy 1997– Of food or drink: extremely appetizing or enjoyable, in a way that encourages overindulgence.

Chief Leader of the Epick Quire [Latin Chori..Epici ] .

The shining Qualitiy of an Epick Heroe, his Magnanimity, his Constancy,..raises first our Admiration.

Then, might our great, Third Edward's awful Shade..Pale, from his Tomb, in Epic Strides, advance.

Uniting the great and sublime of epic grandeur with the little and the low of common life.

Here, there, everywhere it went gleaming where men were thickest, like the hero's helmet in an epic battle.

Some great Princess, six feet high, Grand, epic , homicidal.

The noblest descriptive powers would find a fitting subject in the epic journey of the life savers.

I am allowed to chronicle the epic deeds of the men from Blankshire.

When Francis Parkman went out on the Oregon Trail in 1846, the epic period of French-Scottish-Canadian exploration was over.

An epic feat of engineering.

- epic 1652– Of a person, event, action, etc.: such as is described in epic poetry; suitable for the subject of an epic poem; characterized by heroic and…

- epical 1668– Characteristic of an epic; resembling the style or the subjects of epic poetry; grand in scale or ambition. Cf. epic , adj. B.2.

When University of Florida linguistics professor David Pharies asked 350 sophomores for samples of college slang, here's what he found... ‘Killer’ is a compliment, along with ‘mint, awesome, prime, epic , golden, [etc.] ’.

The world's greatest surfers challenging the world's most epic waves.

Want to look totally epic this year at..the pool?

That's epic , dude.

To hit such epic speeds, the researchers combined seven 200Gbits/sec channels over the top of BT's existing network.

- breme Old English–1400 Celebrated, famous, glorious (only in Old English); hence as a general epithet of admiration: Excellent, good, ‘fine’, ‘famous’; sometimes…

- fair Old English– Beautiful to the eye; of attractive appearance; good-looking. Cf. foul , adj. I.7a. Now somewhat archaic … Of a person, or a person's face, figure…

- goodly Old English– Of a good quality or high standard; splendid, excellent, fine. Now archaic .

- goodful c1275– Excellent, worthy, virtuous.

- noble c1300– Distinguished by virtue of splendour, magnificence, or stateliness of appearance; of imposing or impressive proportions or dimensions. †Also as n. …

- price c1300–1615 As a general term of appreciation: worthy, noble; praiseworthy, commendable; prime.

- special c1325– Exceptional in quality or degree; unusual; out of the ordinary; esp. excelling in some (usually… Of an abstract concept, immaterial thing, etc…

- gentle c1330–1604 Of things: noble, excellent, fine. Obsolete .

- fine ?c1335– As a general term of approbation: admirable; excellent; of notable merit or distinction.

- singular a1340–1712 Above the ordinary in amount, extent, worth, or value; especially good or great; special… Of remedies, medicines, etc.: Excellent; highly…

- thriven a1350–1400 As an epithet of commendation, esp. in the alliterative phrase thriven and thro (see thro , adj.² ): ? Eminent, excellent, worthy, honourable…

- thriven and thro a1350–1450 Origin, status, and meaning uncertain; occurs in the alliterative phrase thriven and thro , always commendatory or honorific, and apparently meaning…

- gay a1375– Noble; beautiful; excellent, fine. More generally. regional in later use.

- proper c1380– Such as a person or thing of the kind specified should be; admirable, excellent, fine; of high quality; of consequence, serious, worthy of…

- before-passing a1382 Excelling.

- daintiful 1393–1440 = dainty , adj.

- principal a1398– Of special quality; excellent, choice; first-class, first-rate. Now rare ( Scottish in later use).

- gradely a1400– Of things. Excellent, suitable, handsome.

- burly c1400–1873 poetic . Of things: Goodly, excellent, noble. Obsolete . (As an epithet of spear , brand , the meaning may have been ‘stout’: cf. boisterous , adj. )

- dainty c1400–1855 Valuable, fine, handsome; choice, excellent; pleasant, delightful. Obsolete or dialect in general sense.

- thriving c1400–1540 In alliterative use: Excelling, excellent, worthy; = thriven , adj. 2, thrifty , adj. 2. Obsolete .

- vounde c1400 (Meaning obscure.)

- virtuous c1425–75 Of high quality, excellent. Obsolete .

- hathel c1440–1540 Noble; worthy.

- curious c1475–1816 Without explicit reference to workmanship: Exquisite, choice, excellent, fine (in beauty, flavour, or other good quality). Obsolete or dialect …

- singler c1500 = singular , adj. , in various senses.

- beautiful 1502– Realizing an ideal of intellectual or moral excellence; pleasing to the mind, esp. in being appropriate or well-suited to a particular purpose…

- rare ?a1534– colloquial . In weakened sense: splendid, excellent, fine. Now chiefly Scottish , Irish English , and English regional .

- gallant 1539– Used as a general term of admiration or praise: excellent, splendid, fine, grand. Cf. brave , adj. A.3. Now chiefly Irish English .

- eximious 1547– Excellent, distinguished, eminent; notable, singular.

- jolly 1548– Used as a general expression of admiration: Splendid, fine, excellent.

- egregious ?c1550– In a positive sense. Of a person, or his or her qualities: distinguished, eminent; great, renowned.

- jelly c1560– Good, worthy, excellent; having a high opinion of oneself, proud, haughty.

- goodlike 1562– Of a good quality or high standard; splendid, excellent, fine; = goodly , adj. 4a. Now Scottish .

- braw c1565– = brave , adj. A.3; worthy, excellent, capital, fine.

- of worth 1576– of worth : valuable, useful, important; of high merit or excellence; worthy. Cf. of value at value , n. phrases P.1.

- brave ?1577– loosely , as a general epithet of admiration or praise: Worthy, excellent, good, ‘capital’, ‘fine’… Of things.

- surprising 1580–1831 Exciting admiration, admirable; occasionally adv. Obsolete .

- finger-licking 1584– a. n. The action or an act of licking the fingers, esp. to remove remnants of food after eating; b. adv. so as to cause a person to lick his or her…

- admirable a1586– Worthy of admiration or praise. In later use also as a general term of esteem or appreciation: excellent, very good, pleasing.

- excelling a1586– That excels; superior, surpassing. Now only in good sense. †Of a number: Exceedingly great.

- ambrosial 1598– In extended or weakened use: extremely beautiful or pleasing; extraordinarily great; excellent, wonderful.

- sublimated 1603– Of a person or immaterial thing: elevated to a high degree of perfection, excellence, or refinement; noble; exalted.

- valiant 1604 Of an item of clothing: splendid. Obsolete .

- excellent 1609– (The current sense; originally a contextual use of 1.) Used as an emphatic expression of praise or approval, whether of persons, things, or…

- fabulous 1609– Such as is met with only in fable; beyond the usual range of fact; astonishing, incredible. Now frequently in trivial use, esp. = ‘marvellous’…

- pure 1609–1888 slang . Fine, good, excellent, nice. Obsolete .

- starry c1610– figurative and in figurative contexts. That shines spiritually, morally, or intellectually; illustrious; excellent, admirable.

- topgallant 1612–1850 Used humorously or poetically as an intensive: = gallant , adj. (in various senses). Cf. sense A.4. Obsolete .

- lovely 1614– In weakened use: excellent; delightful, pleasant, nice; enjoyable. Now also as int.

- soaring a1616– figurative . Rising to a great height, high pitch, etc.; egregious; ambitious, aspiring; sublime.

- twanging 1616 colloquial . Exceptionally fine or good. Cf. stunning , adj. , ripping , adj. , etc. Obsolete .

- preclarent 1623 Excellent.

- prime a1637– colloquial . In weakened or ironic use: excellent, splendid; marvellous. Chiefly in predicative use, or as int.

- prestantious 1638 Characterized by excellence; excellent.

- splendid 1644– Excellent; very good or fine.

- sterling 1647– Of character, principles, qualities, occasionally of persons: Thoroughly excellent, capable of standing every test.

- licking 1648– That licks. Of a flame: = lambent , adj. Also slang , first-rate, ‘splendid’ (cf. thumping , adj. 2, whacking , adj. ).

- spanking a1666– Very big, large, or fine; exceptionally good in some respect, frequently with implication of showiness or smartness.

- rattling 1690– Rapid, brisk, vigorous. Also: remarkably good.

- tearing 1693– Impressive, splendid, grand; ‘ripping’, ‘rattling’, ‘stunning’. colloquial or slang . (Now rare .)

- famous 1695– Used (chiefly colloquially ) as an emphatic expression of approval: Excellent, grand, magnificent, splendid, ‘capital’.

- capital 1713– Excellent, outstanding, first-rate. Frequently as an exclamation of approval. Now somewhat dated .

- yrare 1737– Pseudo-archaic f. rare , adj.¹

- pure and — 1742–1873 pure and — : very, truly; entirely, utterly. Cf. and , conj.¹ A.I.i.5. See also sense B.1. Obsolete ( regional in later use).

- daisy 1757– slang . (chiefly U.S. ). A first-rate thing or person; also as adj. First-rate, charming.

- immense 1762– slang . Superlatively good, fine, splendid, etc.

- elegant 1764– North American and Irish English . As a general term of approbation: very good, excellent, first-rate. Also as adv. Cf. iligant , adj.

- super-extra 1774– Designating a commodity, manufactured goods, etc., of the highest quality; ( Bookbinding ) designating a premium-quality binding, typically with…

- trimming 1778 That trims, in various senses of the verb; making trim, adorning, decorating; clipping, paring; colloquial or slang , ‘stunning’, ‘rattling’…

- grand 1781– colloquial . Used as a general term to express strong admiration, approval, or gratification: magnificent, splendid; excellent; highly enjoyable…

- gallows 1789– dialect and slang . As an intensive: Very great, excellent, ‘fine’, etc.

- budgeree 1793– Good, excellent.

- crack 1793– Pre-eminent, superexcellent, ‘first-class’.

- dandy 1794– Fine, splendid, first-rate. colloquial (originally U.S. ). Frequently in fine and dandy .

- first rate 1799– As an emphatic expression of praise or approval: extremely good, excellent.

- smick-smack 1802– Elegant, first-rate. rare .

- severe 1805– colloquial (chiefly U.S. ). A vague epithet denoting superlative quality; very big or powerful; hard to beat.

- neat 1806– colloquial . Good, excellent; desirable, attractive; (weakened in later use) ‘cool’. Also as int. Chiefly U.S.

- swell 1810– That is, or has the character or style of, a ‘swell’; befitting a ‘swell’. Of persons: Stylishly or handsomely dressed or equipped; of good…

- stamming 1814– Fine, excellent.

- divine 1818– In weaker sense: More than human, excellent in a superhuman degree. Of things: Of surpassing beauty, perfection, excellence, etc.; extraordinarily…

- great 1818– colloquial (originally U.S. ). As a general term of approval: excellent, admirable, very pleasing, first-rate. Cf. sense A.III.13a.

- slap-up 1823– Very or unmistakably good or fine; of superior quality, style, etc.; first-rate, first-class, grand… Of things. Now used esp. of meals.

- slapping 1825– Of persons or things: Unusually large or fine; excellent, very good; strapping.

- high-grade 1826– gen. Of a high grade or standard; good quality.

- supernacular 1828– Esp. of drink: excellent, superb, outstanding. Cf. supernaculum , n. B.3.

- heavenly 1831– colloquial . In weakened sense: excellent, wonderful, very pleasant.

- jam-up 1832– Usually jam-up . Excellent, perfect; thorough. colloquial .

- slick 1833– First-class, excellent; neat, in good order; smart, efficient, that operates smoothly; superficially attractive, glibly clever. (Of things, actions…

- rip-roaring 1834– Full of energy and vigour; boisterous, wildly noisy; first-rate, exciting.

- boss 1836– attributive . Of persons: master, chief. Of things: most esteemed, ‘champion’. Now esp. in U.S. slang : excellent, wonderful; good, ‘great’; masterly.

- lummy 1838– First-rate.

- flash 1840– Of a hotel, etc.: First-class, fashionable, ‘crack,’ ‘swell’.

- kapai 1840– Good, fine; excellent; very pleasant.

- slap 1840– = slap-up , adj.

- tall 1840–52 figurative . Great in quality, excellent, good, first-class. ( U.S. slang .)

- high-graded 1841– = high-grade , adj. (in various senses).

- awful 1843– colloquial . In emphatic use. Cf. sense B Used to emphasize something enjoyable or positive; excellent, first-rate, tremendous.

- way up 1843– Far up; very high up.

- exalting 1844– That exalts (in various senses of the verb).

- hot 1845– Characterized by intensity or energy, in a positive or neutral sense (cf. sense A.II.9); exciting… colloquial (originally U.S. ). Extremely good…

- ripsnorting 1846– = rip-roaring , adj.

- clipping 1848– slang . Excellent, first-rate.

- stupendous 1848– In weakened sense: extremely good or pleasing; marvellous, splendid.

- fly 1849– Chiefly U.S. (esp. in African American usage). Stylish, sophisticated, fashionable; attractive, good-looking; (later also more generally)…

- stunning 1849– colloquial . Excellent, first-rate, ‘splendid’, delightful; extremely attractive or good-looking.

- raving 1850– colloquial (originally U.S. ). Worth raving about; superlative, stunning.

- shrewd 1851– As an intensive, qualifying a word denoting something in itself bad, irksome, or undesirable: Grievous… ‘Hard to beat’, formidable. rare .

- jammy 1853– Covered with jam, sticky. Also figurative ( colloquial ), excellent; very lucky or profitable; easy, ‘soft’.

- slashing 1854– Very large or fine; splendid. Now chiefly Australian .

- rip-staving 1856– Boisterous, rollicking; impressive, excellent. Also as an intensifier. Cf. rip-roaring , adj. , ripsnorting , adj.

- ripping 1858– slang . Excellent, splendid; ‘rattling’. Now somewhat archaic .

- screaming 1859– transferred and figurative . slang . First-rate, splendid.

- up to dick 1863– slang and regional . up to dick : up to a proper or high standard; excellent; (also) properly, suitably; excellently; to a high standard.

- nifty 1865– Chiefly U.S. Smart, stylish; attractive; of good quality.

- premier cru 1866– A growth or vineyard that produces wine of a superior grade; the wine itself. Also in extended use and figurative . Cf. cru , n. , growth , n.¹ 1d and…

- slap-bang 1866– = slap-up , adj. a.

- clinking 1868– slang . Used intensively, as adj. or adv. , like chopping , clipping , whacking , rattling , etc.

- marvellous 1868– colloquial . In weakened sense (formerly sometimes regarded as an affectation in speech): extremely good or pleasing; splendid.

- rorty 1868– Boisterous, rowdy; saucy; jolly, cheery. Also: dissipated, profligate; (of a song, story, etc.) lively, risqué; (of a drink) intoxicating.

- terrific 1871– As an enthusiastic term of commendation: amazing, impressive; excellent, exceedingly good, splendid.

- spiffing 1872– Excellent, first-rate, very good, etc.; fine or smart in, or with regard to, dress or appearance. Also as adv.

- top tier 1879– Of or belonging to the highest or upper level, class, or grade; first-rate.

- all wool and a yard wide 1882– Phrases and proverbial sayings. (a) against the wool : contrary to the direction in which wool naturally lies, the wrong way. (b) to draw (pull, †spr …

- gorgeous 1883– colloquial . Used as an epithet of strong approbation. (Cf. splendid , adj. )

- nailing 1883 colloquial . Good, excellent. Obsolete . rare .

- stellar 1883– Having the quality of a star ( star , n.¹ I.4); leading, outstanding. Originally and chiefly U.S.

- gaudy 1884– slang . In negative sentences: Very good.

- fizzing 1885– slang . First-rate, excellent; chiefly quasi- adv.

- réussi 1885– Fine, excellent; successful.

- ding-dong 1887– colloquial (originally English regional , later chiefly Australian ). Excellent, great; extraordinary; exciting.

- jim-dandy 1888– Remarkably fine, outstanding.

- extra-special 1889– Applied to a special extra (sometimes the latest) edition of a newspaper, etc. Also as n. : such an edition. Hence transferred and figurative …

- yum-yum 1890– Excellent, first-class; delectable.

- out of sight 1891– slang (originally U.S. ). Excellent, incomparable, wonderful, extraordinary. Cf. outasight , adj.

- high-calibre 1893– a. Of a high standard; high-quality; (of a person) highly capable; very skilled, experienced, etc.; b. (of a gun) having a large bore or calibre…

- outasight 1893– Excellent, incomparable; = out of sight , adj. B.2. Also as int. : fantastic.

- smooth 1893– Superior, excellent, ‘classy’; clever, ‘neat’. colloquial (originally U.S. ).

- top-of-the-basket 1894– Of high calibre; excellent; outstanding.

- corking 1895– Unusually fine, large, or excellent; stunning. Also adv.

- large 1895– slang (originally and chiefly U.S. ). Of a period of time: enjoyable, exciting; excellent.

- super 1895– Of a product, model, etc.: that is of the highest quality or is especially well designed for its purpose.

- hot dog 1896– North American slang . Of outstanding quality or merit; skilful; flashy, ostentatious.

- bad 1897– As a general term of approbation: good, excellent, impressive; esp. stylish or attractive.

- to die for 1898– colloquial (originally U.S. ). to die for : (chiefly used predicatively) as if worth dying for; extremely good or highly desirable. Also in to die …

- yummy 1899– Delicious, delectable; also as int.

- deevy 1900– ‘Divine’; delightful, sweet, charming.

- peachy 1900– colloquial (originally U.S. ). Excellent, marvellous, great; (of a woman) attractive, desirable.